Former White House Chief of Staff Karl Rove said in November that Republicans and Democrats are in an arms race for data that will determine the course of American elections.

Over the past two decades, candidates from the two parties have worked to amass as much information about their constituents as humanly possible to put them at the greatest advantage to win elections and influence voters. They’ve done this using our voter registration records, census data, purchase histories, and social media profiles.

University of Texas journalism assistant professor Samuel Woolley says candidates now have a new tool in their arsenal to collect data: their own campaign apps. These applications, and most notably the Trump campaign’s official app, are collecting a wealth of information not just about their users but also about everyone they come into contact with — so much so that they could, in fact, replace traditional social media as the preferred tool for collecting data about voters.

Woolley, who is part of the university’s Good Systems grand challenge network, joined us to talk about these apps, what kind of data they collect, and why we should be wary of them.

Can you tell me a little bit about the rise of these campaign apps? What kind of data do they collect, and what did you find when you compared the Official Trump 2020 and the Team Joe apps?

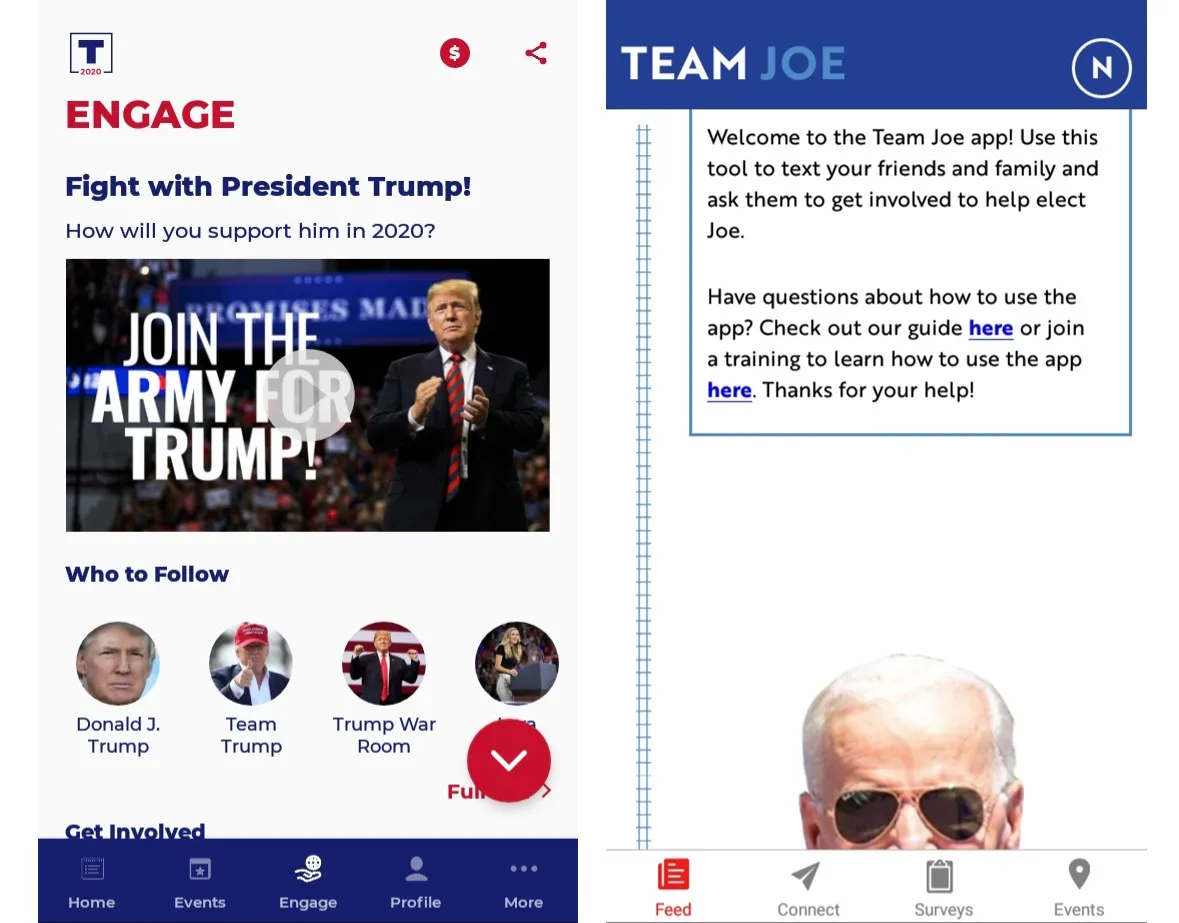

Sure, so campaigns have been making use of various social media platforms and different software applications for several years now. But this year in the United States, we’re seeing the emergence of special official campaign apps that both the Joe Biden and President Donald Trump campaigns are using in an attempt to reach voters. These are apps that you install on your phone.

The Trump app and the Biden app are two very different beasts. The Trump app is almost like a one-stop shop. People can sign up to volunteer, get tickets for events, and get news. Very rarely does it have a byline, and it usually tends to be interviews of internal Trump people. A lot of it is actually pretty misinformative. The Trump app, unlike the Biden app, also stores and keeps the user’s contact data. Then, they can then reach out to all those people.

The Biden app is more of a traditional voter outreach app built very much on the Obama model, which has to do with relational organizing and connecting with people. That means the app prompts you to send text messages to people in your contacts it thinks may be persuaded to vote for Biden. It’s definitely got its own issues, but it’s clear that the Biden app is built with a lot of intentionality when it comes to the data that the campaign team can access. For instance, the app doesn’t store people’s contact information.

We, as a team, have been focused on the ways in which these applications may or may not be collecting unnecessary amounts of data.

In particular, when we did an analysis of the Trump app, we found that it basically amounts to what I would call nefarious surveillance or manipulative surveillance. We find that it asks for way more permissions from your phone — information on your precise and approximate location through GPS, the ability to read your phone status and identity through its unique device number, the ability to pair with Bluetooth devices and geolocation beacons and even read, write, or delete from SD cards in the device.

Why should we be concerned about this?

People might be thinking, “Who cares if it connects to your Bluetooth signal? Who cares if it gets GPS access?” The argument that we’re making is that this is a new era of hyper-personalization. People are giving up their own locations, which leads to information about where they spend their time. Do they go to church? Do they go to the shooting range? Do they go to Planned Parenthood? Bluetooth beacons can be placed anywhere to target people who walk near them. I’m picking particularly political examples, but if you know this kind of information about people, you can target them with specific messaging.

One of the criticisms of this is: who cares about campaign apps, and who is going to put these on their phones? So far, Trump’s app has garnered fewer than 100,000 downloads. Yes, it’s the most diehard supporters that download them, but those diehard supporters are connected to hundreds of other people. So, not only does the app have access to the person but also all of their contacts, and they can begin building a database based on their interests, where they spend their money, and a lot of other data points.

The Trump app, in addition to simply asking for access to people’s contacts, also stores and externally keeps that information so it can build a collection of data over time. It’s not an immediate process. For instance, say the campaign gets access to my cell phone number, and another associated political group is like, “Hey, we have his email and a bunch of information from his Facebook account that we got during the 2016 election.” Now we can add this to his voter profile, and the campaign or PAC can store that internally, then use that information as intelligence for how we attempt to contact and advertise to him in the future.

With these applications, we’re seeing more of a shift toward hyper-personalized advertising, tracking of people’s location or what I call geo-propaganda, or the arrival of broadscale surveillance in political campaigns.

The advent and rise of these campaign applications is an attempt to circumvent traditional social media platforms because Facebook and Twitter and YouTube have all been tightening up their restrictions. Twitter has been tagging Donald Trump’s posts and calling out misinformation. The applications are a way for the campaign to have a captive audience.

With these applications, we’re seeing more of a shift toward hyper-personalized advertising, tracking of people’s location or what I call geo-propaganda, or the arrival of broadscale surveillance in political campaigns.

Will these apps replace social media for data gathering, or are they being used in addition to those platforms?

Both traditional social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter and campaign applications have a use to political campaigns. Still, I view this as a shift — a kind of experiment to see how successful campaigns can be with building out their own internal walled-off campaign apparatus to communicate directly with their most hardcore supporters while gaining access to a larger audience. As one person put it to me, this is a way to approach micro-targeting through different means where campaigns no longer need Facebook or Twitter to do the micro-targeting for them because they hold all the data.

This means they can circumvent any kind of regulations, correct?

Yeah, precisely. The other thing is that there’s no fact checking that occurs in these campaign applications. The self-regulation that social media companies impose does not exist in these applications. We’re seeing progress on social media, which has been achingly slow, sure, but it’s still progress. But it’s basically being leapfrogged by this new technology that keeps it within the campaign, so to speak. It’s not to say that the government couldn’t come up with regulations or policy to police this, it’s just that there’s no political appetite for that right now.

What can be done about this data gathering? What’s the solution?

From a policy perspective, governments should start working to put limitations on campaigns’ use of political applications. For instance, governments have limitations on campaign finance that they could also put on campaign communications. They could say, “If you’re a political campaign in the United States, you can’t gather location data on people. You can’t ask for access to contacts. You can’t do this and that.” So, we need policy at the federal level to actually address how campaigns can use these tools. Right now, there is none.

Some states like California and governments like the European Union are leading the way by passing their own data gathering laws, which require sites to disclose that they’re gathering cookies and things like that. So, there’s some movement at the state and municipal levels.

We have seen some movement, too, in the last couple years at the federal level with the emergence of bipartisan work on bills related to data gathering like the Shield Act, which is meant to protect our elections from foreign interference and disinformation campaigns. But that is languishing right now in committee because even though Republicans and Democrats can agree that we don’t want our data to be gathered and used against us, that we don’t want this invasion of privacy to happen, Congress is in such a gridlock and things are so polarized under the current administration that there’s no political will to push it forward.

In addition to policy, we also need more robust tools to help us analyze the way these applications work. Technology-based solutions work in the short term to analyze algorithms, but you also need human labor — and that’s where the education component comes in. We need to reinvest in people so they can create new models and work to fight back against this stuff. But that’s a more long-term solution.

What role do we have to play as voters and consumers of information?

Media literacy has also got to play a role. I think that the fact that we’re here having this conversation is a good sign. When I tried to talk to people about propaganda on social media 10 years ago, they were they were really unengaged. Now, everyone wants to talk about it. So, we made progress. I do anticipate, though — depending on what happens in November and in the next 40 years — that there will have to be data laws passed in this country. It’s just a matter of time.

Read more about Woolley and his team’s research into campaign apps in this recent MIT Technology Review article.