When Building Community Resilience is the Goal, Community-Based Participatory Research is the Methodology of Choice for Planet Texas 2050 Collaborators

You may have recently noticed research groups in Waller Creek, the meandering waterway passing through the Forty Acres. Indeed, it should come as no surprise to find research being conducted anywhere on the campus of one of the leading public research universities in the world. What distinguished these groups, though, were their makeup. Researchers as young as 7th grade students, all the way to societal-leading professors from The University of Texas at Austin were collaborating as part of the Planet Texas 2050-supported 2024 Climate Justice with Youth Summer Institute.

Their mission? To co-design and research arts-integrated climate literacy curriculum in K-12 education. The group was proactively learning about the creek’s unique ecosystem and its history and drew inspiration from its natural beauty for the serious business that lay ahead of them.

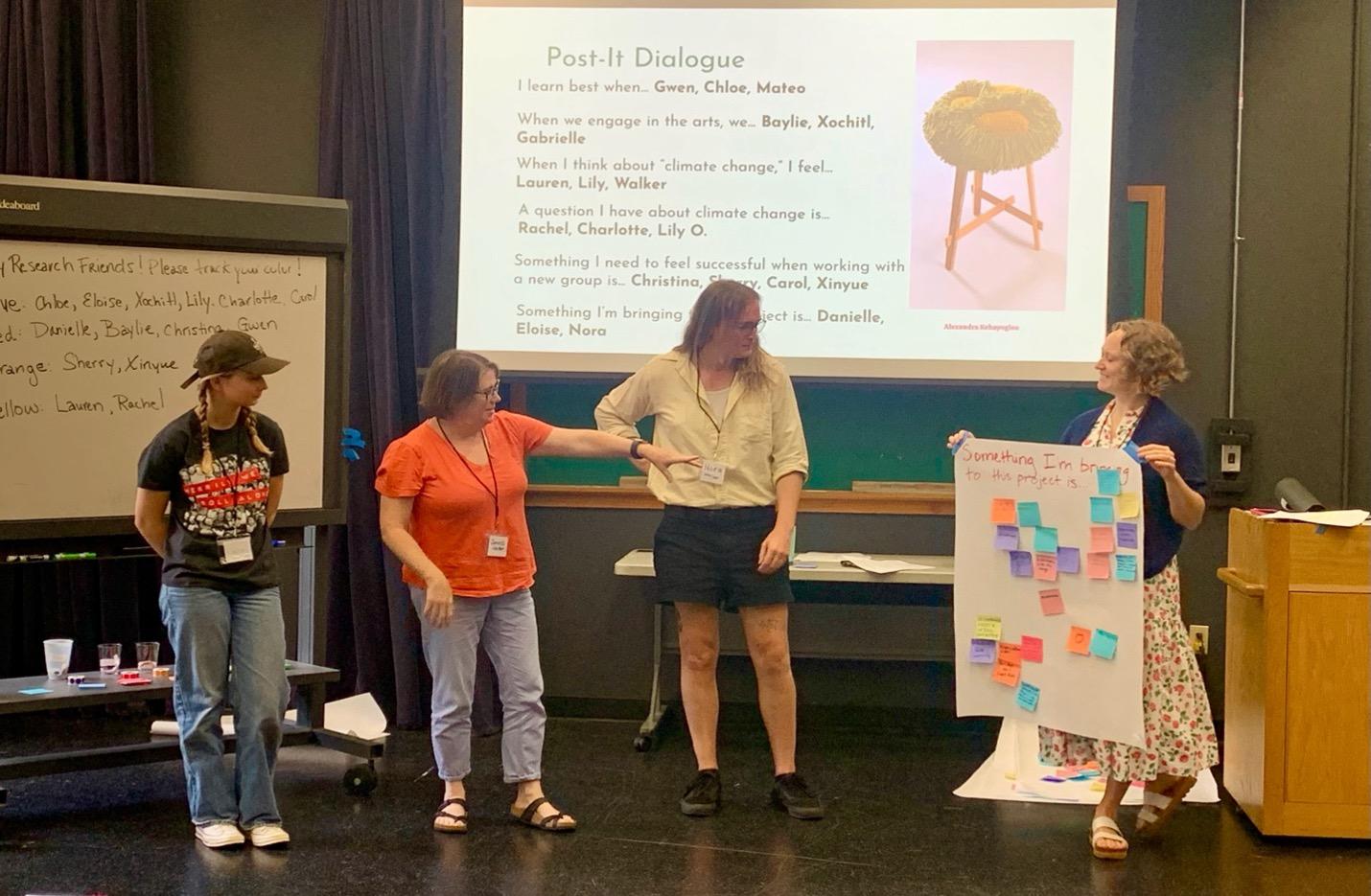

Now in its second year, the goal of Climate Justice with Youth Summer Institute is ambitious: to design a new climate change justice 7th grade curriculum in collaboration with Ann Richards School for Young Women Leaders. Instead of using traditional pedagogical methods, the new interdisciplinary curriculum is grounded in inquiry-based arts practice — theater, dance and visual arts — to increase moments of critical and creative thinking and learning.

“Our focus is on innovative educational practices, youth empowerment through research and the integration of arts with community engagement in educational settings.”

— Katie Dawson, associate professor, Department of Theatre and Dance

The list of experts working together appears, ostensibly, to be an educational hierarchy of expertise: middle and high school students, middle school teachers, UT researchers, and university professors. But there’s one crucial difference: all enter the project on an equal footing.

“Our focus is on innovative educational practices, youth empowerment through research and the integration of arts with community engagement in educational settings,” said Katie Dawson, associate professor at the Department of Theatre and Dance, who, along with assistant professor of Theatre and Dance, Lara Dossett, and Stephanie Cawthon, professor at the College of Education, helped bring this project together.

Research or Outreach?

Who knows more about Waller Creek, a celebrated limnologist with decades of academic experience studying the characteristics of inland fresh-water systems or a lay person who has lived on the banks of the creek their entire lives?

Trick question. The answer is both. PT2050 is frequently focused on building the resilience of communities within their own environments. Since local people often possess a kind of expertise only gained through lived experience, they may be able to provide researchers with knowledge that helps to generate more nuanced and impactful research questions. In other words, combining the expertise of both allows you to understand the challenges faced more holistically.

Grounded in a specific research methodology known broadly as community-based participatory research (CBPR) — a method of inquiry whereby academic researchers work in tandem with community members to address bespoke research questions — Drama for Schools uses different forms of CBPR including Youth Participatory Action Research (YPAR) with students and Participatory Action Research (PAR) with educators.

CBPR aims to avoid what is sometimes referred to as "helicopter research," where academics might rely on local expertise for a study but once the data gathering phase is complete, so too is any role the community might have played. Reducing community participants from authorities to data points, even unintentionally, can diminish research impact, and often breeds suspicion towards well-intentioned academic researchers among local populations.

“One of the challenges we face as researchers is that traditional scientific methods are largely based on Western theories that were not conceptualized with diverse populations in mind.”

— Carmen Valdez, professor, Dell Medical School

CBPR engages community members at every stage, from problem identification to implementation. By prioritizing community-driven responses and outcomes, this methodology aligns perfectly with an interdisciplinary initiative like Planet Texas 2050.

Misperceptions of CBPR

The method has, at times, come under scrutiny. By taking a more focused, people-centered approach, CBPR can be incorrectly conflated with outreach or service. “Traditionally, CBPR projects will engage with historically marginalized communities, and in our case, particularly with young people,” said Miriam Solis, whose focus is on Community and Regional Planning at UT’s School of Architecture.

“So it is often assumed to be some kind of youth support or outreach program. This simply isn’t the case.”

Unlike community outreach, which primarily involves providing services or information to a community, CBPR is a collaborative research methodology. Where outreach is typically one-directional, CBPR fosters a two-way exchange of knowledge and expertise between researchers and community participants.

Another misperception is that the central role played by community members in the design and implementation of the research dilutes its scientific rigor or validity.

“One of the challenges we face as researchers is that traditional scientific methods are largely based on Western theories that were not conceptualized with diverse populations in mind,” said Carmen Valdez, a professor with dual appointments at Dell Medical School and the Steve Hicks School of Social Work.

“Incorporating knowledge derived from diverse populations actually strengthens the research and promises to increase uptake of findings, which is key in translation of research to practice.”

Case Study: Visualizing Voices

Valdez and Solis have been collaborating, through Planet Texas 2050, for several years on a project working with communities in Austin and the Rio Grande Valley to effect change in their local built and natural environments. They are conducting research and gathering qualitative data on everything from extreme heat to mental health.

Solis focuses primarily on environmental and climate justice in communities facing acute local challenges, such as proximity to industrial pollutants affecting air and water quality or limited access to green space.

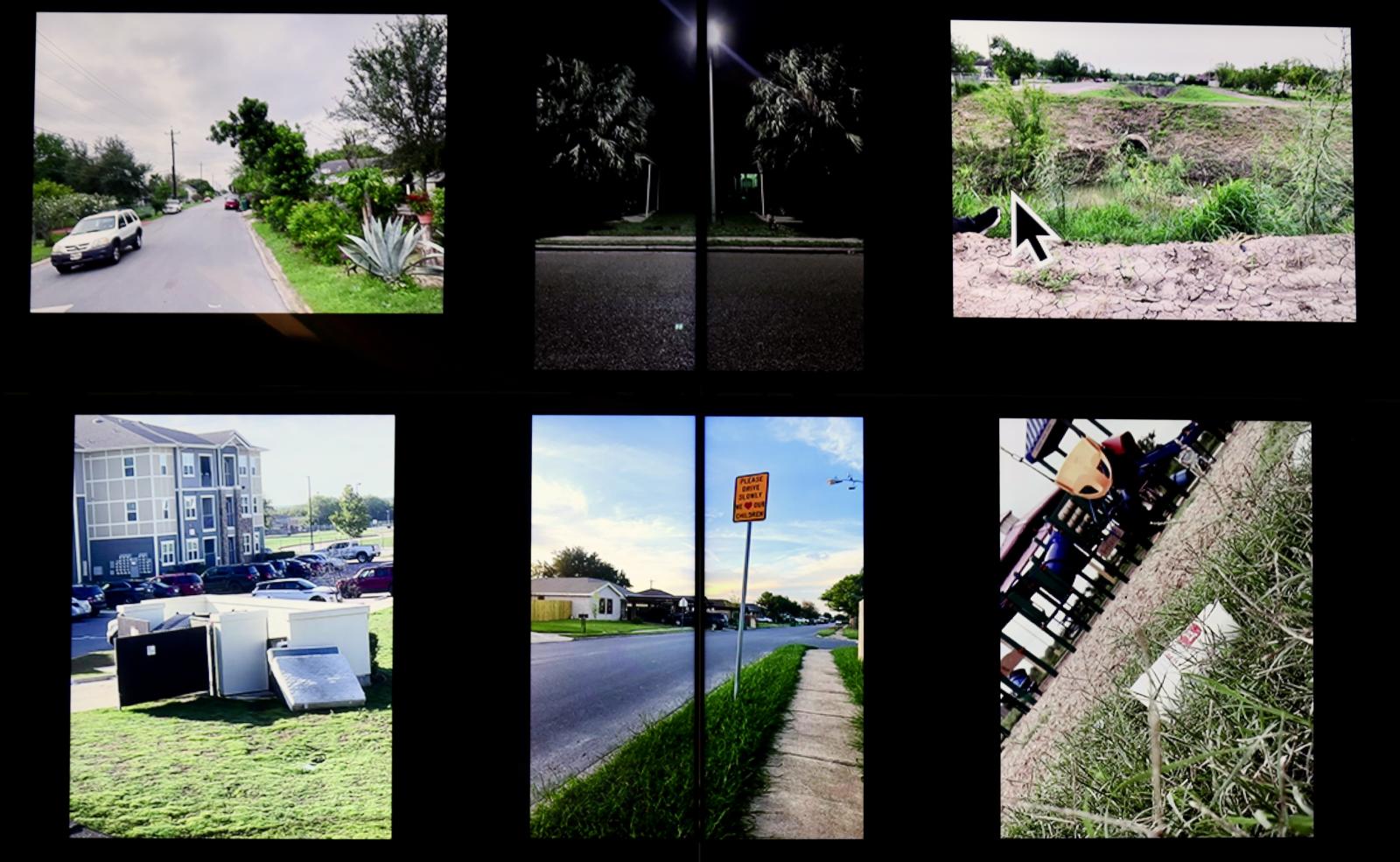

In 2023, Solis and Valdez facilitated a “photovoice” exhibition in Pharr, in Texas’s Rio Grande Valley. This CBPR method involves participants capturing local photos and writing narratives, translating experience into actionable knowledge. They saw its potential to include traditionally excluded groups, like youth, in important dialogues in both Austin and Pharr.

“Young people are rarely consulted on how climate change has impacted their community’s environment,” Solis said. “Offering them alternative ways to enter the conversation through tools like photovoice can be an effective way to learn from their insights.”

An exhibition called "Looking to the Future,” showcasing local high school students’ perspectives on environmental challenges and injustices in the Rio Grande Valley, debuted in Pharr in 2023 and was featured at Texas Advanced Computing Center’s (TACC) Visualization Lab during the 2024 PT2050 Symposium. The exhibition is part of Valdez and Solis’s broader “Planning with the Future” project, which documents their research-practice partnership with the Pharr community. The aim is to understand youth experiences of environmental burdens, strategize for a just climate transition, and support environmental improvement through coalition-building.

Case Study: Climate Justice with Youth

At the 2024 Drama for Schools and Creative Learning Initiative Summer Institute, held in June at the Department of Theatre and Dance, high school students and teachers worked in tandem to develop a course outline. Through CBPR, the conventional classroom dynamic was flipped on its head. “It does require teachers to put their egos to one side,” said Baylie Head, a theater teacher at Ann Richards. “You learn to value student input more, and it removes some of the preconceived notions teachers may sometimes have about the importance of being the intellectual authority on all things.

“Traditional curriculum planning excludes students from the process. Including them in the design process inevitably leads to greater engagement with the topic from the class generally and provides insight into what will work for them and for their teachers.”

Lily Rerecich, a sophomore at Ann Richards who participated in the summer institute and will serve as a research and teaching assistant once the program is rolled out, appreciated the CBPR-based course design.

“Climate justice is one of the most important issues for my generation,” Rerecich said. “I want to be an ornithologist when I finish high school, but I also love art. So the integration of science and the arts is a really clever way of engaging students on this important topic.”