UT Austin’s Bridging Barriers Research Grand Challenges have demonstrated the value and impact made possible by interdisciplinary collaboration.

Environmental engineer Paola Passalacqua first met public policy professor Patrick Bixler at the dissertation defense of a student neither of them knew. They were both on the evaluation committee, Passalacqua representing the Cockrell School of Engineering, Bixler the LBJ School of Public Affairs.

“He’s asking questions I like,” Passalacqua said of Bixler. “And our questions fit together very well, even though I’m a hydrologist and he’s a social scientist. So when they asked me to lead a Planet Texas 2050 project and find a co-lead, I thought of him.”

That was 2018. They have since joined forces on five projects through Planet Texas 2050, one of UT Austin’s three Bridging Barriers Research Grand Challenges.

It’s not always that easy. So, instead of depending on the serendipitous meeting of two colleagues at a dissertation defense, Bridging Barriers has taken a structured, proactive approach to interdisciplinary collaboration.

“Bridging Barriers gives you a chance to say, ‘Who would you want to work with?’ I would have probably never co-led a project with a social scientist without the opportunity. It’s not something I would have thought to do. But it gave me a chance to do that.”

— Paola Passalacqua, Planet Texas 2050 chair

Passalacqua, who has been involved with Planet Texas 2050 since its inception, acknowledges her meeting with Bixler may have been serendipitous, but it takes a lot more than a chance encounter to nurture the kind of working relationship the two UT researchers now enjoy.

“[Bridging Barriers] gives you a chance to say, ‘Who would you want to work with?’” Passalacqua said. “I would have probably never co-led a project with a social scientist without the opportunity. It’s not something I would have thought to do. But it gave me a chance to do that.”

The vision for Bridging Barriers, when it was conceived almost eight years ago, was to network scholars together across colleges, departments and disciplines to leverage UT’s resources and expertise and advance research on major societal challenges. At the outset, faculty provided input on areas they felt would benefit from collaboration. This bottom-up approach has been critical to the success of all three grand challenges: Planet Texas 2050, Good Systems and Whole Communities–Whole Health.

Three Grand Challenges

Planet Texas 2050 is a solutions-based project helping Texans adapt and build resilience in response to rapid population growth and climate change in the Lone Star State.

Good Systems focuses on the ethics of artificial intelligence. By asking not what AI can do, but what AI should do, the collaborative team explores ways to ensure the technology is designed to benefit everyone in society.

Whole Communities-Whole Health aims to understand how physical and emotional adversity, biology, and the environment affect the health and well-being of children and their families.

Interdisciplinary Encounters

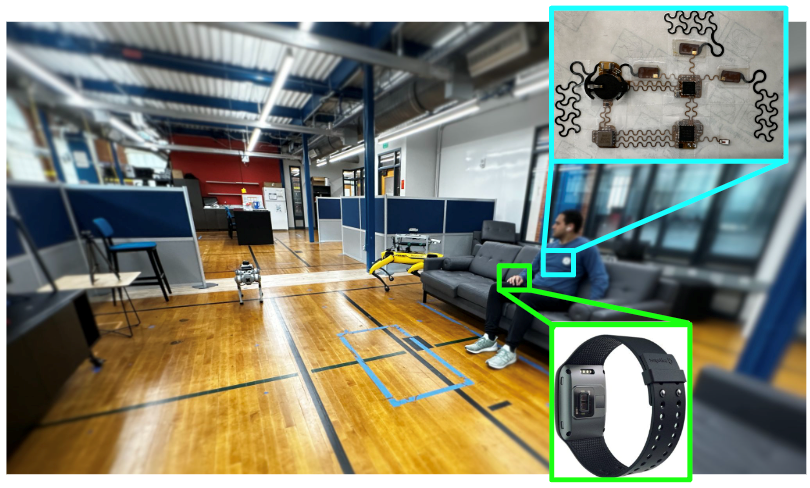

Having an interdisciplinary team working on Good Systems’ study about creating safer and more ethical robots proved critical to effective data collecting. The research team needed to collect four different types of data: self-reported data, interview data, human electrocardiogram and electrodermal (or sensor-based) data.

Collecting these data required collaboration among multiple campus units, including Texas Robotics, the Cockrell School of Engineering’s departments of Aerospace Engineering and Engineering Mechanics and Biomedical Engineering, the Moody College of Communication and the Texas Advanced Computing Center.

“The team was able to triangulate the data and see that when sensor data suggested a human-experienced stress — like when a person thought two robots might collide — the qualitative and self-reported data agreed,” said Keri Stephens, professor of communication studies at Moody and co-lead on the project.

The study is funded as part of the National Science Foundation’s Growing Convergence Research program, which supports research that transcends disciplinary boundaries. “This is a clear example of when interdisciplinary research is needed to solve complex problems, and it provides a clear example of team and data convergence,” Stephens said.

To catalogue the extensive data collected in this project, colleagues from TACC created knowledge graphs to show the project's details and where and how collaboration led to innovation. TACC is currently working to create a platform to share the data.

Compounding Flooding Expertise

The convergence of challenges faced by communities in the Beaumont-Port Arthur region requires equally diverse areas of expertise. Led by Passalacqua, Planet Texas 2050 and Whole Communities-Whole Health researchers at UT, Lamar University, Texas A&M University, Prairie View A&M University and Oak Ridge National Laboratory are collaborating with local community members to operate the Southeast Texas Urban Integrated Field Lab (SETx-IFL). The SETx-IFL team — funded by the Department of Energy — is working on the ground to collect data and find practical solutions for local communities affected by air pollution and flooding.

“When you have social scientists, data scientists, engineers and other stakeholders working together from the beginning, that’s more effective collaboration,” Passalacqua said. “We all have to be at the table together.”

At the SETx-IFL table, all of the above sat down with members of the nearby community to design the optimum approach for collecting and analyzing data to identify equitable adaptation strategies. Factors such as geography, risk level, socioeconomic determinants and population density must be considered before placing sensors in an urban setting. Aside from simply locating the most flood-prone areas, Passalacqua says the group accounted for stakeholder input, social vulnerability and information from past floods to identify the areas most in need.

“Which areas are most vulnerable, and what, if any, preventative measures are already in place?” she said. “Were they or were they not covered by flood insurance in the past? When you answer these kinds of questions too, it often leads to different, more holistic conclusions than if we were to take a purely scientific approach.”

The Air We Breathe

From indoor and outdoor air and water quality to sleep patterns and stress levels, researchers from Whole Communities–Whole Health work closely with local community members to identify and investigate social and environmental factors impacting health. WCWH has been assessing the role of indoor environmental exposures — specifically the quality of air and potable water — on our physical and mental health.

To assess indoor air quality in participants’ homes, researchers use sensors, or beacons, to determine the concentrations of particles and carbon dioxide in the air. The beacons also measure temperature and relative humidity levels to understand heat exposures.

In addition, they are collecting home dust samples to determine microbial (bacteria and fungi) and chemical contaminants such as plasticizers, flame retardants and other “forever chemicals” present in our homes.

While scientific expertise frequently underpins the technical design of sophisticated measurement tools for air and water quality, access to the homes of communities most in need of such technologies requires other skillsets.

“Engineers like myself work with researchers from social work, healthcare, psychology and education to develop partnerships with historically marginalized communities,” said Professor Kerry Kinney from Cockrell’s Maseeh Department of Civil, Architectural and Environmental Engineering.

WCWH also relies heavily on its Community Strategy Team. “This group, composed of community members from the Del Valle region of Austin, works closely with UT researchers to determine what questions the community are most concerned about, and helps guide researchers on how best to engage, inform and return their findings to the local community,” Kinney said. “Without everyone’s input — from the community and across campus — a project as wide in scope as WCWH would simply not be possible.”

"All three Grand Challenge topics were entirely driven by the researchers themselves, and I think this is why they have been so successful.”

— Jennifer Lyon Gardner, Deputy Vice President for Research

Staying Power

Almost eight years after its creation, Bridging Barriers has developed a network of over 300 scholars that includes students, postdocs and research staff, and spans nearly every college and school on campus and research support units like TACC, UT Libraries and the Office of Sustainability. Over the years, the network has expanded beyond campus to include collaborations not just across disciplines but also across industry, state officials and local communities.

“All three Grand Challenge topics were entirely driven by the researchers themselves, and I think this is why they have been so successful,” Deputy Vice President for Research Jennifer Lyon Gardner said. “Many of the original architects for each are still on their respective steering committees today, are still working with the Grand Challenge, and leading many of its efforts all these years later. It's a true testament to having that buy-in from the very beginning.”

The opportunities open to faculty and researchers willing to work beyond their own discipline continue to grow in a funding landscape increasingly enthusiastic about interdisciplinary methods. “Collaborations across disciplines can take a lot of work, especially in the early stages,” Gardner said. “Large scale, community-engaged research requires persistence and teamwork. But, as we’ve seen, the payoff can be significant.”