“The earth’s a big blue marble when you see it from out there… The sun and moon declare… our beauty’s very rare.”

In 1974, towards the end of a time when the sobering consequences of the Vietnam War had dominated TV, a show called the Big Blue Marbledebuted for children. The name was a nod to a photograph of the earth taken by the crew of Apollo 17, and its underlying themes were peace, love, nature, cultural awareness, and the importance of togetherness.

Today, on Earth Day, the “sobering war” that pervades our media is the COVID-19 pandemic, and the coverage has contributed to a new global awareness of infectious diseases. We see, hear, and read about the weaknesses and strengths of our health systems and the importance of scientific research at a global level to expedite the development of new diagnostics, drugs and vaccines. That’s because it’s clear to many people now, more than ever, that we must prepare as much as we can for the inevitable outbreaks of infectious diseases that we are certain to face in the future. While we are all collectively focused on the threat presented by the novel coronavirus’ risks right now, we must not forget that the viruses and bacteria that cause human illness are organisms that live alongside us in a natural environment that is rapidly changing due to climate change — and that climate change mitigation must be considered as an element of preparation.

Earth Day gives us the opportunity to reflect on how efforts to preserve our natural environment and invest in green technologies, like sources of renewable energy, might also increase our resilience to future pandemics. Such reflection is critical at a time when we are confronted by the dual threats of disease outbreaks and climate change, threats that are connected by the fact that our fight against climate change is also a battle to prevent an upending of the ecosystems in which humans, animals, plants, viruses, bacteria, and parasites coexist. When we recognize how these threats are connected, it’s possible to appreciate how actions taken to minimize climate change, like reducing green house gas emissions, also represent a way to protect against increased global risk of acquiring certain diseases.

While the factors influencing human exposure to disease is complex, we know that climate plays a crucial role in determining where disease-causing agents and the animal vectors that often distribute them can survive. According to the WHO, climate change is predicted to cause approximately 250,000 additional deaths per year from 2030-onward. In the last decade alone, serious mosquito-borne illnesses like zika and chikungunya, which are typically restricted to tropical areas of the world, have started to appear in the far southern reaches of the continental U.S., gaining considerable media attention. At the same time, however, other diseases new to our country have not been as publicly acknowledged.

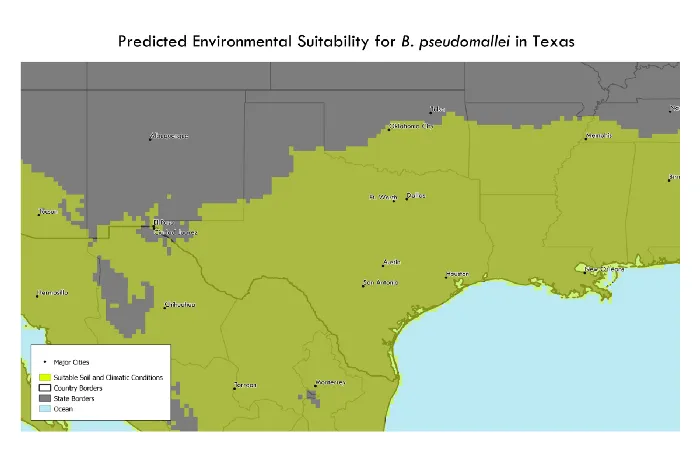

Our own research is currently focused on using geospatial analysis to identify where Burkholderia pseudomallei, the bacteria that causes the disease melioidosis, might be located in areas outside of the tropics. Geospatial analysis involves study of the geographic patterns and relationships associated with the spatial distribution of features or phenomena across the Earth’s surface, such as the distribution of COVID-19 seen in the now well-known map produced by Johns Hopkins University, and it is often used to help us understand why things are found in particular places and determine where we can expect things to appear.

Melioidosis is an often severe and sometimes fatal neglected tropical disease, primarily contracted through contact with contaminated soils and water. Why study this in Texas? Because Texas has recently been identified as the first state in the U.S. mainland endemic for a disease that’s most commonly found in the tropics. Melioidosis is still relatively unknown in many areas of the world today but was familiar amongst physicians treating military personnel who contracted the disease during the Vietnam War. They sometimes became ill after returning home, giving rise to the name “Vietnam’s time bomb.”

However, we no longer have experts in the U.S. trained to identify melioidosis, so its recent emergence will demand more awareness by public health authorities in regions deemed to be of higher risk for contracting the disease such as subtropical regions of Texas and possibly other Gulf Coast states. This example helps explain why research aimed at predicting where diseases — which are restricted to specific regions of the world today — might appear under future climate change scenarios can help us prepare for, and hopefully prevent, future disease outbreaks. This approach ensures that we can quickly and correctly identify diseases when they begin appearing in new areas and take appropriate measures to curtail their spread and impact. But to do so effectively requires that we not lose this legacy of global awareness once the current pandemic recedes.

COVID-19 has given us an opportunity to change how we perceive the impact of infectious disease. Why? Because it affects us all. So, too, will the diseases that we start to see spreading as our climate changes. We must recognize that efforts taken to improve the health of the planet we live on are also efforts to protect our own health, and that such efforts will demand a continued “togetherness” on a global scale. As a line from a Big Blue Marble song states, “Together is a word that holds tomorrow in its hands.”