We’re often asked why advancing technology is so critical to our mission of working together with Central Texas communities to build a more complete picture of health. Now, the COVID-19 pandemic has elevated the importance of technology as we lean on it to teach, work, learn, and connect with each other. Whole Communities–Whole Health has been listening to local families impacted by the upheaval of this public health crisis. Like so much in the world right now, our plans are changing in response to what we hear. But one thing has become clear: providing access to quality data — clear information about our participant’s physical, environmental, and community health — has never been more important. This story, compiled before the crisis hit, highlights how we’re committed to developing technology that puts information about indoor air quality into the hands of the people who can use it most.

— Frances Champagne, Professor

Chair, Whole Communities–Whole Health

May 2020

In January, Margarita García stood over a hot griddle, roasting cocoa beans to make a fine chocolate.

Outside, the Oaxacan air was cold. But inside, the comales where the beans were cooking warmed the tiny brick-and-mortar room that houses the Lanní chocolate factory.

García removed the wood from the comales, since only coals are needed to roast the beans, releasing swaths of smoke into the air, which filtered out the open windows and into the downtown square.

University of Texas engineering students were visiting the southwest Mexican town as part of a study abroad experience, organized by International Engineering Education and the nonprofit “Tejiendo Alianzas,” to meet and learn about underserved communities. They crowded around García, watching as she moved the cooked beans from the griddle to a table to grind them, then roll them into bon bons.

In a corner of the room, a device created by UT engineers, known as a smart home beacon, measured the particulate matter in the air — in this case, the thick gray smoke. It picked up spikes in the particles.

Left unchecked, these particles, like those found in everyday American homes, can become lodged in the lungs and contribute to serious health problems, including respiratory conditions, heart disease, diabetes and even depression.

“A lot of diseases are linked to particulate matter in the air, especially indoors, where we spend more than 90% of our time,” says Juan Pedro Maestre, Ph.D., a research associate in UT’s Department of Civil, Architectural and Environmental Engineering, who attended the Oaxaca trip as scientific adviser and is responsible for testing the home beacon. Particulate matter can even affect memory when small particles get into a person’s bloodstream. “It has very relevant health implications.”

The small Mexican chocolate factory, led by three indigenous women, is just one place researchers have brought the beacon — trying it out before they offer it to dozens of families in eastern Travis County in the coming years to better understand how their indoor environment can affect their health.

The home beacon is part of a research initiative known as Whole Communities–Whole Health, a UT grand challenge. A grand challenge brings together researchers from different disciplines whose experiences build upon one another’s to address an urgent societal concern. In this project, the interdisciplinary team is collaborating with community members and organizations to design a 5-year cohort study in order to understand more about the physical, environmental, and emotional health of families typically underrepresented in traditional research.

Technology will be a core component of the study, said David Schnyer, Ph.D., a cognitive neuroscientist and one of the founding researchers of the Whole Communities–Whole Health team. This differs from traditional health studies, he says, because in those, researchers get information by asking participants to come in for a health exam once or twice a year or fill out surveys every few months. Those things are helpful, he explains, but the surveys are subjective — the answer someone gives depends upon their own perception of the question — and they’re too infrequent. They don’t give a full picture of someone’s life.

“What we are getting is snapshots with very little information about what is happening in these in between periods that could be more important in terms of understanding the effects of adversity on development,” Schnyer adds.

By employing technology like the home beacons, researchers can get a window into homes in real time so they can understand how environmental factors like indoor air quality affect family health. In turn, they hope to give that data back to the communities in a way that is understandable and actionable so they can make better decisions about their health now, rather than in several years when the study is complete.

The Building of a Home Beacon

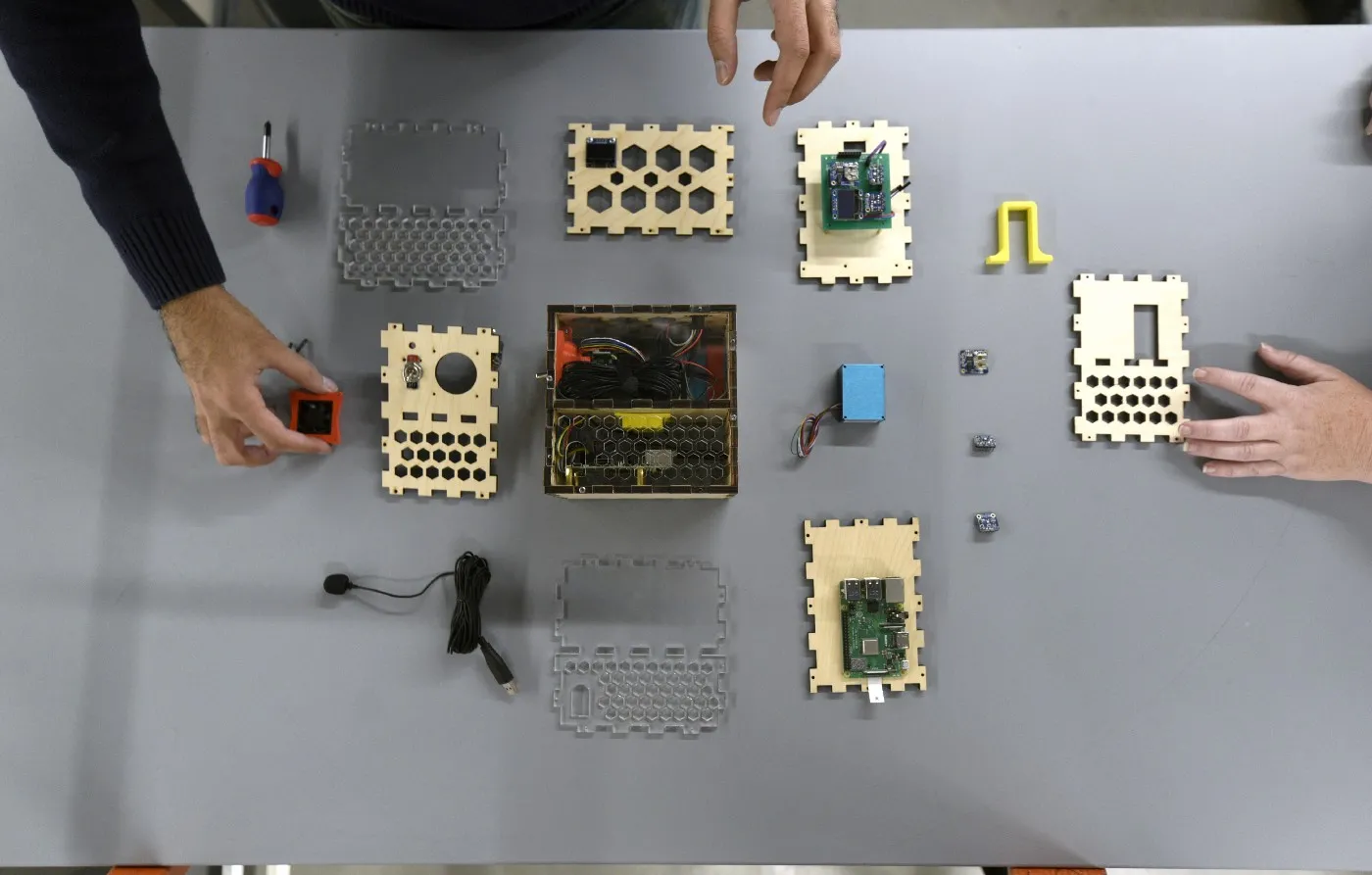

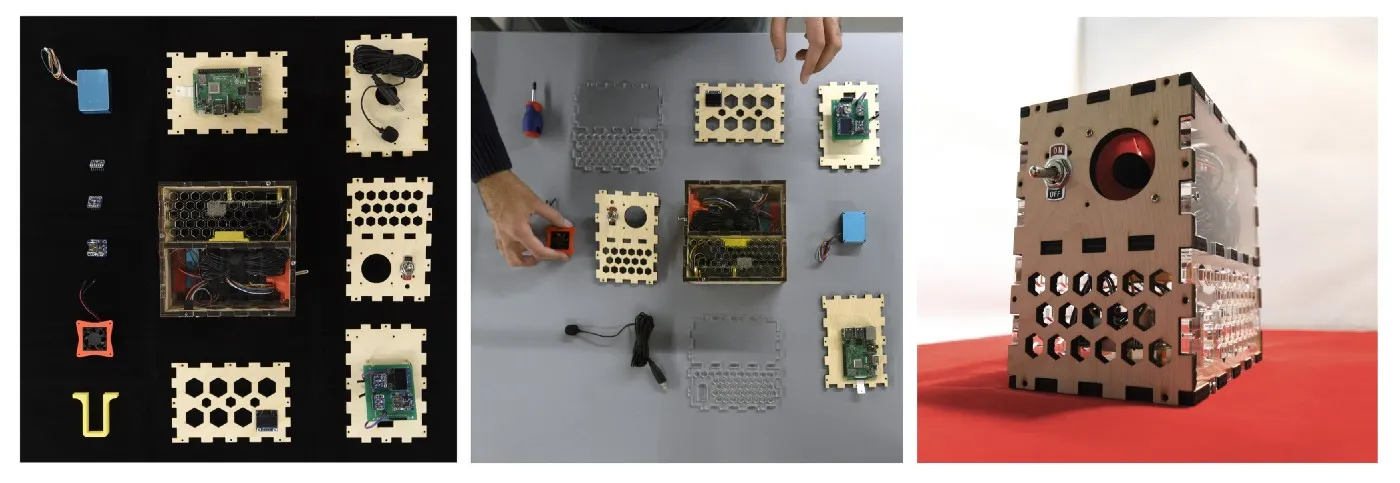

In the Intelligent Environments Laboratory in the basement of the Cockrell School of Engineering, graduate research assistant Sepehr Bastami in 2018 put together the first iteration of the home beacon: an acrylic and black plastic device packed with small sensors to measure temperature; relative humidity; total volatile organic compounds, including those in cleaning products; and particulate matter, or things like dust or smoke from cooking.

Bastami says the beacon often overheated when it spun up, which affected its readings, but it was functional enough to begin testing. That year researchers used it to better understand the home air quality of a handful of psychology students as part of a broader study known as UT 1000.

“The student tests were kind of like a preliminary, debugging time,” graduate research assistant Hagen Fritz says of the project. “We were checking and calibrating the sensors [in the home beacon], making sure we were getting reliable data… to make sure everything was working right. Then, we could tailor it before we made it available to the community.”

Fritz and Bastami have updated the beacon significantly since its testing debut two years ago. They switched the casing from plastic to wood and added fans so the device won’t overheat. Community advocates weighed in on the beacon’s design as well. They asked for a transparent cover and an LED screen so they could observe the readings — and they asked for an off switch, too. Fritz also added more and better sensors, including new ones to measure light, carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide and nitrogen dioxide, which — at higher levels — can have adverse health effects, including reduced cognition. He explains that having this information is critical to mitigating some of the main drivers of poor health in families.

“Anything that burns, like cooking, lighting a candle or smoking inside is going to produce some level of carbon monoxide and particulate matter, which will affect lung development and lung function,” Fritz says. “In kids, that can decrease their lung growth and can lead to complications later on in life.”

When the final version of the home beacon is completed, a smartphone app will allow participating families to see their indoor environmental data and make changes in their home if they notice anything awry. Resources on the app might encourage families to make small changes that can make a big difference, like opening a window or turning on a fan when cooking.

However, in some cases, more comprehensive policy changes may be needed, the researchers say, including in those areas near power plants or factories or that see heavy construction, where air pollution is much higher and beyond their individual control.

“In some areas, there are just poorer quality buildings, lower quality water and air,” Bastami says. “For some of these communities, if you have better information, concrete evidence of systemic inequities and challenges… maybe something could change on a higher level. Maybe more attention is paid to these communities.” That’s the goal.

When all is said and done, the project hopes to bring together information from across the community to create a clearer picture of the area’s health challenges and successes. In turn, community organizations and policy-makers will have better data to point to as they advocate for positive systemic changes.

The Whole Communities–Whole Health cohort study will focus on residents in eastern Travis County, and engaging with this community has been critical for researchers, who — when designing the grand challenge — wanted to be sure they asked participants what they wanted to know about.

“Traditional science will sort of swoop into a community, gather some people together, have them sign some forms, collect some data, go away, maybe come back at different time points in the future, collect some more data, go away. That data then is analyzed, examined and published and discussed in scientific forums, but most of the community members are sort of left behind feeling, ‘What was that all about?’” Schnyer says. “Our approach was to engage the community from the start, ask [them], ‘What is it you want to know about yourself and your own lives?’ And then figure out what is the best way we can get that information to them.”

The project has required electronics, software, and medical experts to come together with members of the community to listen and learn from each other in unprecedented ways and lend their various expertise.

“Human problems are always complex, and complex problems require interdisciplinary work,” Bastami says. “You have electronics people making it more reliable, medical professionals telling you what that data means, and software people putting it all together and sending it out. You have to have all these people, or it’s just a numbers generator.”

The beacon is designed and built as open hardware, meaning the concept can be picked up by research labs across the country — another important point for UT scientists. They hope that, whatever they accomplish with the smart home project, it can be duplicated and even improved in other places, perhaps even in the indigenous communities in Mexico, where Maestre took the beacon to test it.

“We know that health inequity is a significant problem, not only in the U.S. but also worldwide,” Schnyer adds. “There are people who believe the ticket to solving health inequity is going to be in [technology]…I’ve gotten very excited in my own work about the ability to use these particular devices in order to understand how people live in real time and give that information back to families in a way that’s usable.”