'What has gotten into you?”

If you’ve ever been a child, chances are your parents said something to this effect (or at least wondered it) when you threw a tantrum. Maybe you’ve said (or wondered) the same thing as a parent yourself.

Adam Grabell — an associate professor in the department of psychological and brain sciences at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and the keynote speaker at this year’s WCWH showcase — conducts research that helps answer that exact question. Grabell studies how emotion regulation — essentially, how people control their feelings — works in early childhood, particularly for children who might be at risk for future mental health problems.

We interviewed Grabell ahead of next month’s showcase to learn more about his work, exploring how he studies emotion regulation in young children, what factors influence it and how his research could help kids in the future.

Your research focuses on “emotion regulation and its relation to cross-diagnostic symptoms of psychopathology in early childhood.” Could you translate that for a layperson?

By emotion regulation, I mean how human beings control their feelings. In other words, when you feel an emotion, the ability to change how intense that emotion feels, how long it lasts or whether the emotion is positive or negative. Studying emotion regulation in early childhood is really interesting because, in general, most 3- and 4-year-old children are not very good emotion regulators, as any parent will tell you. They are still learning how to control big feelings like frustration.

At the same time, very poor emotion regulation in early childhood, such as being really irritable, or having really bad tantrums, is a symptom we see show up in over a dozen mental health disorders, from problems with aggression to problems with anxiety or mood (hence, the “cross-diagnostic” part). But if all young children are just learning how to control their feelings and have tantrums sometimes, how do we know when emotion regulation problems should be labeled a concern? That’s one of the main questions my lab is interested in.

Tell us more about the SEED Lab? What kinds of studies are you conducting? What are the different ways your lab goes about measuring emotion regulation?

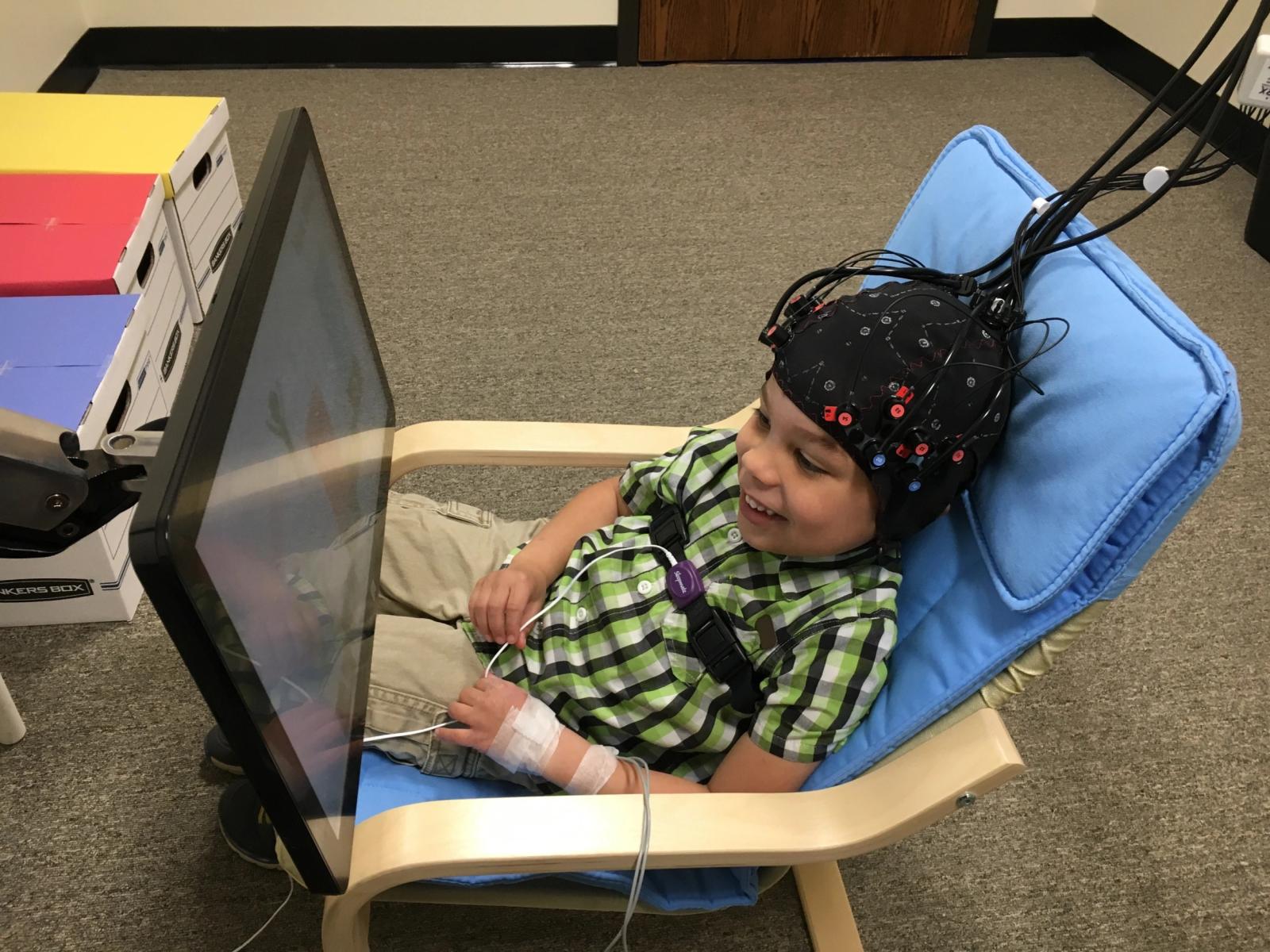

The SEED lab does “lab-based” research and “home-based” research. In our lab-based research, we bring preschool kids in, hook them up to a bunch of sensors (such as brain sensors), and have them play exciting and frustrating games while we carefully monitor how they are dealing with emotions.

But more recently, we’re doing home-based research, and this is mostly the focus of my WCWH talk. In our home-based studies, all the research happens in families’ homes, neighborhoods and communities. Parents might download an app designed to detect early mental health problems, or children and their parents wear wearable devices for a month so we can track emotion regulation as it naturally happens in everyday life. These home-based approaches are exciting because they can go places and reach people in a way that lab-based research can’t, which could help us develop better tools to detect and treat early mental health problems someday.

Home-based approaches are exciting because they can go places and reach people in a way that lab-based research can’t, which could help us develop better tools to detect and treat early mental health problems someday.

How are children currently identified as being at risk for mood and behavior problems? What have you and your team learned that could help identify and treat those children?

The current status quo of the child mental health system and how at-risk children are identified is a major reason we do the work we do. For the most part, in order for a young child to receive a diagnosis that could be used to start therapy or receive accommodations, they must first do a clinical intake with a licensed provider. That intake might involve interviews, observations, tests or filling out lots of questionnaires. The problem is that getting to this intake usually means being on a clinic waitlist for months, making sure you have the right insurance, transportation, childcare coverage, knowledge of the system and trust of that system. As a result, a lot of parents are stuck in this “wait and see” phase for years — years when that child could have started an intervention already.

That’s why we are working on these mobile home-based tools to measure early emotion regulation problems. These tools could make it a lot easier for caregivers to get initial information about their child’s level of risk, change the way they seek help and hopefully allow them to start a treatment much earlier compared to the current status quo.

So far, we are finding evidence that more mobile tools can measure emotions and mental health in the home under a wide range of conditions, but there are certainly shortcomings and limitations. And, perhaps somewhat surprisingly, when you ask working clinicians what they think about all this, you get a very wide range of opinions. Some clinicians see the creation of mobile tools as essential, others see it as not a good idea, and everyone has their own opinion of who should control and administer these tools, should they ever exist. All of which means that, even if we got mobile mental health tools to work perfectly for young children, figuring out how to make them a reality is going to be really complicated.

Adam Grabell works with a student at his SEED Lab at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. (All photos courtesy of Dr. Grabell)

What environmental factors have the most effect on children’s emotion regulation, both inside and outside the home?

The most powerful influence on children’s emotion regulation inside the home is how their caregivers are parenting them. Caregivers who are more abusive and do not yet have the skills to consistently follow through with household rules and routines tend to have children with poorer emotion regulation skills. But it also goes the other way, where having a child with emotion regulation problems makes it harder to be an effective parent. It’s one reason most of the therapies we have for early emotion regulation problems focus on the caregiver, on changing the dynamic of that caregiver-child relationship.

The most powerful influence on children’s emotion regulation outside the home is societal inequality and injustice. Societal inequality includes poverty and structural discrimination, such as institutional racism. Poverty and discrimination deprive families of necessary resources for healthy child development, such as access to nutrition and quality education, placing families under tremendous and chronic stress that significantly and negatively impacts their health. Unfortunately there is no intervention a therapist can administer to relieve problems happening at this scale.

What initially sparked your interest in studying emotion regulation, particularly in young children?

In college I was a psychology major and loved it, but after graduating I had no idea what I wanted to do and just moved back home. After a few weeks of sitting on the couch, my mom told me I had to get a job, and the first one I found was in a preschool in my town. I worked there for about a year, and for most of that I had my own preschool classroom where I was the head teacher.

By spending every day with the same group of kids, I got to know them all very well; I also saw how some of my kids already had more difficulties with their emotions and behaviors, and I thought deeply about why this was the case. I also got to see, first-hand, how dramatically children at this age change over the course of just a year. It was an incredible experience, and I still think about the kids in my class. In my mind, they are all still 3 to 5 years old!

Adam Grabell, Ph.D., is an associate professor in the department of psychological and brain sciences at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, and the principal investigator of the Self-regulation, Emotions, and Early Development (SEED) lab. His talk, “Automated, home-based mental health tools: a new way to reach and help at-risk families,” is the keynote address at WCWH’s annual showcase, which is free and open to the public. Register here to attend.