How the ‘First Big Win for Planet Texas 2050’ Has Bolstered Community Preparedness in Austin

On a seasonably blistering afternoon last September, residents and community leaders gathered at the George Morales Dove Springs Recreation Center in southeast Austin to celebrate a milestone nearly a decade in the making. The room was abuzz, the Tex-Mex was plentiful.

The event marked the official launch of the Resilience Navigation Portal — the culmination of more than four years of research and five years of collaboration between Planet Texas 2050 (PT2050) and Dove Springs residents. The interdisciplinary network formed through PT2050 played a critical role in developing the project and securing external funding.

Supported by a National Science Foundation (NSF) grant and developed through UT Austin’s first externally funded interdisciplinary Bridging Barriers project, the portal is designed to help communities prepare for, respond to and recover from climate-related disasters. It integrates top-down data from city and county sources with hyper-local information shared by Dove Springs residents, enabling them to better navigate emergencies such as floods, heatwaves and once-unprecedented events like Winter Storm Uri, which left 40% of Austin Energy customers without power and caused $195 billion in damages.

“One of the amazing things about the Bridging Barriers programs is that they give you space and time to develop these community-engaged projects, which are slower than traditional research because you have to build trust and relationships.”

— Katherine Lieberknecht, School of Architecture

The portal reflects not only technological innovation but a deep investment in community trust and collaboration — it is about community engagement, resilience and the kind of interdisciplinary work the Office of the Vice President for Research, Scholarship and Creative Endeavors’ (OVPR) Bridging Barriers Grand Challenges were created to foster. “One of the amazing things about the Bridging Barriers programs is that they give you space and time to develop these community-engaged projects, which are slower [than traditional research] because you have to build trust and relationships,” said Katherine Lieberknecht, the project’s principal investigator (PI) and an associate professor in the Community and Regional Planning program at the School of Architecture.

“We all put in a lot of time and effort and thought, but we also had all this support from Planet Texas 2050,” Lieberknecht added. “[OVPR Deputy Vice President] Jennifer Lyon Gardner being there at those meetings and saying, ‘Whoa, how about a different track? Try thinking about it this way.’”

A Portal Born from Data and Community

The Resilience Navigation Portal traces its origins to the Texas Metro Observatory (TMO), an early PT2050 project dedicated to analyzing Texas’s metropolitan areas. By examining shared resource challenges across the state, TMO’s metro analysis demonstrated a need for community-specific disaster preparedness tools.

From the start, the project was interdisciplinary by design. The original team of five PIs represented five different colleges and areas of expertise: urban planning (Lieberknecht), civil engineering (Fernanda Leite) communication studies (Keri Stephens), computing and data visualization (Suzanne Pierce, from the Texas Advanced Computing Center (TACC)) and public health (Lourdes Rodríguez, previously of Dell Medical School). This range of expertise allowed the team to bridge data, design and community engagement in meaningful ways. “It was an amazing group of people that came together,” Leite said.

Drawing from their diverse strengths, they focused on a shared challenge: how to translate statewide data into tools that serve the needs of real communities. Nearly 90% of Texans live in metro regions, where climate disruptions such as floods, extreme heat and ice storms can have devastating effects.

"You can get that level of granularity if you're able to connect with the residents that understand their neighborhood."

— Fernanda Leite, Cockrell School of Engineering

"We wanted to think about different ways of telling that story,” Lieberknecht said, referring to Texas’s rapid urbanization and the need to tell more human-centered stories about how people live, work and face climate challenges in those areas. “What does economic development look like there? What do environmental resources look like there? Through that work, we really started to understand that there's so much information we're constantly generating as academics, as scholars, as researchers. But how do we make that data public facing in a way that's compelling and useful and helpful to practitioners and community members and NGOs and local governments? That's what we tried to get at with the Texas Metro project."

The Observatory’s findings played a key role in securing one of the first competitive Smart and Connected Communities (S&CC) grants from the NSF. According to Leite, "It was the very first big win for Planet Texas 2050."

Bridging Hyper-Local Knowledge with Big Data

One of the biggest challenges the project faced was downscaling climate models to the neighborhood level. Most climate models provide broad projections for large geographical areas that don’t account for local realities: where specific intersections flood, which homes are most vulnerable to extreme heat or how people actually respond to disasters. In short: How do you make broad climate models useful to neighborhoods like Dove Springs?

Leite explained that the project allowed residents to provide hyper-local input that traditional climate models miss. For example, while flood simulations typically operate at the city level, local residents understand exactly which streets flood during heavy rains and how these "nuisance floods" — more frequent, less severe flooding events — affect their daily lives.

“You can get that level of granularity if you're able to connect with the residents that understand their neighborhood,” Leite said. “So, we built this portal with support from TACC to be able to collect these data and train local residents to try to understand, 'What does that all mean for them?’”

But data alone wasn’t enough. Solutions had to be developed with the people most affected, not just for them. That became especially clear when GAVA (Go Austin / Vamos Austin), a community organization deeply embedded in Austin's Eastern Crescent, approached the research team with a pressing concern.

"What I’m most proud of is how the community feels ownership over this project. It’s not just something we gave them — it’s something they helped shape from the very beginning of the project.”

— Keri Stephens, Moody College of Communication

Dove Springs, a predominantly Latine neighborhood, had been hit hard by climate events like the Halloween floods of 2013, when water from nearby Onion Creek rose 11 feet in 15 minutes, damaging more than 1,200 homes and killing four people. The disaster highlighted a practical problem: despite information available from various agencies, residents needed a central, user-friendly resource to help them prepare for and respond to emergencies — what Lieberknecht referred to as a "one-stop shop" for disaster preparedness.

“We are proud that community members have ownership in this product,” Stephens said. “What researchers often do is, we create systems and then we kind of superimpose them on the community. Our approach in this project was to make sure that whatever we develop for the community has their input in it and their guidance throughout the whole process. This is real community-engaged research.”

Tú-Uyên Nguyễn, a climate resilience community organizer with GAVA, emphasized the grassroots nature of the portal. “My favorite thing about this project is that it started with the residents,” she said. “It’s their ideas — what they are seeing, living, needing — every single day.”

‘The Power of People and Relationships’

At the heart of the project were the Climate Navigators — a group of 30 Dove Springs residents, most of them Spanish-speaking women, trained by GAVA to help their neighbors prepare for disasters. Modeled after community health workers, the Climate Navigators became trusted local leaders, guiding their community through the complex terrain of climate resilience.

Stephens said that building trust was key. “What our research is uncovering is that people have individual knowledge bases, but trying to figure out how to share it with your neighbors and share on a community-wide basis is really hard, especially in this type of a community, where there have been historical injustices,” she said. “They don't necessarily always trust city organizations, and furthermore, they don't always trust the University of Texas, because there's also history there as well. To overcome these issues, in the first year of the project, we spent a lot of time building trust, and we went to many community events.”

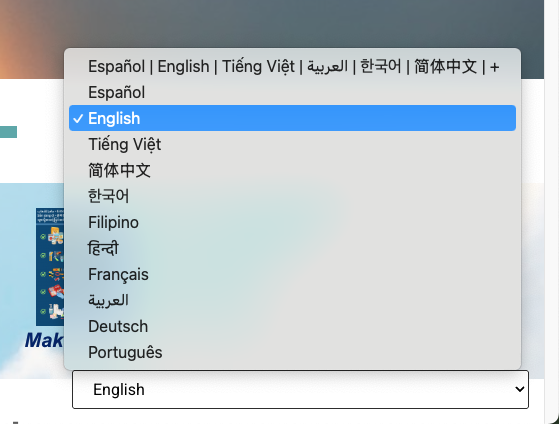

One key design principle was inclusivity, which is especially important given the diverse, multilingual communities who populate the Eastern Crescent. For example, Nguyễn recommended displaying each language in its native form — Español for Spanish, Tiếng Việt for Vietnamese — instead of using English translations.

Ultimately what set this project apart, Nguyễn said, was the ripple effect. “Each leader is representing like a village of people,” she said. “Every single person is connected to family members — siblings, cousins, aunts, uncles, neighbors. And that's the beauty of this whole process, the power of people and relationships.”

Andrea Cruz, a UT graduate student who worked on the project for three years, said that those relationships helped keep the project grounded and collaborative. “It was really nice to have this partnership,” she said. “I learned so much from the community and the people from GAVA.” That connection, she added, made it easier to respond to shifting needs and help the work progress smoothly.

Scaling a Community-Based Model

With the portal now hosted by the Community Resilience Trust (CRT), the next step is expanding its reach. CRT is overseeing the final phase of development and exploring how the platform might be adapted for other neighborhoods or even citywide use.

“The thing that keeps the [project’s] light on, the flame on, is that it was built on trust,” Nguyễn said. “The fact that these are resident leaders... giving feedback and co-creating this work with their priorities. And the fact that they were able to connect to three to five other people in their network — that creates a special relationship with the portal that I don't think exists with the city, for example.”

“The thing that keeps the project’s light on, the flame on, is that it was built on trust.”

— Tú-Uyên Nguyễn, Go Austin / Vamos Austin

"What I’m most proud of is how the community feels ownership over this project,” Stephens said. “It’s not just something we gave them — it’s something they helped shape from the very beginning of the project.”

“The potential is really exciting,” Nguyễn added. “I can't wait to see how the portal continues to grow.”