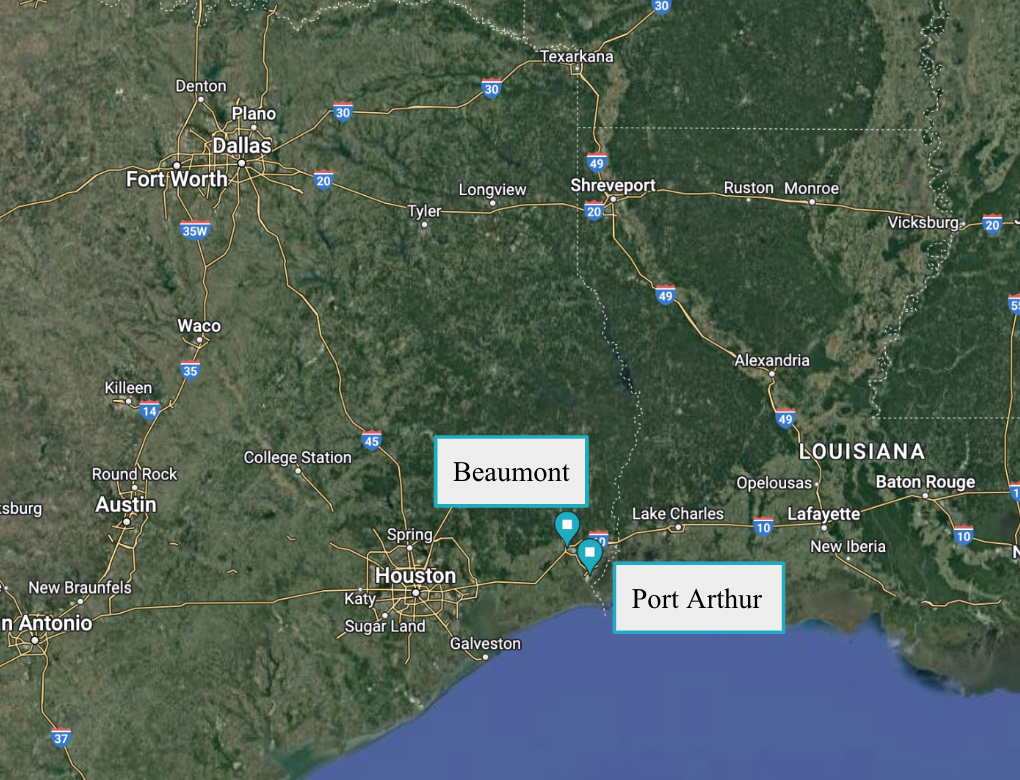

Hurricane Harvey was a storm like no other. In August 2017, more than 26 inches of rain were unleashed in just 24 hours—almost 50 inches by the storm’s conclusion—submerging Beaumont, Port Arthur, and other Texas Gulf Coast cities. Beaumont mayor Becky Ames described the devastation as “nothing I’ve ever seen before.” Flooding in Beaumont spurred the loss of the city’s primary and secondary water supplies. The storm damaged over 200,000 homes, three quarters of which did not have flood insurance. The flooding and winds also led to the release of 5.5 million pounds of pollution - caused by the damage to dozens of nearby petrochemical plants on the coast. More than 80 lives were lost.

Hurricane Harvey wasn’t a normal event. The rainfall recorded, and the extent of the damage, shattered previous records. But the tropical storm was an indicator of a broader weather pattern for the region: according to NASA, the intensity of hurricanes in the Texas Gulf Coast is increasing. Local communities must now try to adapt to a changing climate.

Climate models can envision how long-term weather patterns may change or become more intense in the future. Often, when we think of climate modeling, our minds go to scientists and mathematicians analyzing complex data about our oceans, atmosphere, and land cover. It wasn’t always this way. For millennia, weather and climate were not under the purview of scientists at all, but rather farmers and indigenous populations. Today’s climatologists, engineers, and planners are beginning to acknowledge the value of this indigenous and agricultural insight.

The Southeast Texas Urban Integrated Field Laboratory (SETx-UIFL)

The Department of Energy (DOE) has funded four laboratories hoping to redefine the term “climate model” and help determine who has the tools and information necessary to protect the communities most at risk from climate change. The University of Texas at Austin is part of one such laboratory: the Southeast Texas Urban Integrated Field Laboratory (SETx-UIFL), which also includes Texas A&M, Prairie View A&M, Lamar University, the DOE’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory, and residents in the Beaumont-Port Arthur area. SETx-UIFL is located in Jefferson and Orange Counties, Texas.

These efforts are focused on the Beaumont-Port Arthur region because it is both socially and environmentally vulnerable, as well as a blueprint for the likely challenges facing communities in the future. Beaumont-Port Arthur’s location along the Texas Gulf Coast makes it susceptible to hurricanes, tropical storms, and flooding. It is also home to large oil and gas reserves, adding another element of environmental risk. During large storms or flood events, refineries may be damaged, resulting in oil spills or dangerous chemical releases of sulfur dioxide, benzene, and other chemicals that can cause short- and long-term health problems. As land in the area is developed and paved, these flooding issues will likely increase in severity.

Air pollution is a chronic stressor for the community, and that is compounded when flooding strikes.

Many of the residents in the Beaumont-Port Arthur region lack the economic resources to deal with these environmental threats. A quarter of the families in Port Arthur live in poverty. As reported by the Washington Post, its Black and Latino residents, on average, experience chronic health risks at a much higher rate than the rest of the country, likely as a result of their proximity to toxic emissions. The NRDC reported that cancer and mortality rates for Black Jefferson County residents are 15 and 40 percent higher, respectively, than Texas’s averages. The Center for Disease Control data from 2021 indicate that the rate of chronic kidney disease is 63 percent higher than the state average among residents of the Port Arthur metro area. Environmental justice advocates refer to neighborhoods like those in Port Arthur as “fence-line communities,” alluding to the oil refinery fence lines adjacent to their homes. The increasing intensity of hurricanes and tropical storms will likely amplify the unjust impacts of these disasters.

In September 2022, the DOE announced that it would be funding SETx-UIFL, a five-year $17M investment. SETx-UIFL is focused on understanding and planning for future risks and impacts of both flooding and air pollution in the Beaumont-Port Arthur region. “Air pollution is a chronic stressor for the community, and that is compounded when flooding strikes,” said Paola Passalacqua, the SETx-UIFL lead PI and an associate professor at the Cockrell School of Engineering at UT Austin. “During flooding events there can be major chemical releases into the air and the soil. For both flooding and air pollution, we lack information on what is going to happen under future climate scenarios and how to prepare for that.”

Map of the Beaumont-Port Arthur region. Source: Google Earth

Planet Texas 2050

Collaborations across institutions and disciplines, such as SETx-UIFL, don’t come about without an existing culture that values and actively promotes interdisciplinary research. At UT, that culture is embodied by Planet Texas 2050 (PT2050), an interdisciplinary initiative dedicated to finding solutions to perhaps the biggest grand challenge of our time: how we adapt and thrive in the face of increasing climate change and population growth.

Passalacqua, SETx-UIFL's lead PI, is also the current chair of PT2050, and recognizes the important role local communities must play in any research process that ultimately impacts them. “What is notable here is that SETx-UIFL doesn’t rely solely on large-scale technical information to fill these knowledge gaps," she said. "When developing climate models, the team also plans to incorporate the knowledge of residents who live with the very issues being studied. Collaborating with residents—from community leaders and activists to local scientists and engineers—will shape the kinds of data included in the climate models, and how the infrastructure solutions explored here align with the community’s values. It’s our belief that this collaborative design process will result in a final product that better serves residents in the Beaumont-Port Arthur region.”

Three interdisciplinary teams—created by tapping into existing collaborative networks, including those cultivated by Texas Target Communities, a Texas A&M-based community engagement program, and the Southeast Texas Flood Coordination Study group—will carry out this project. The environment team—a technical task force comprised of flooding and air quality experts—is focused on developing detailed climate scenarios modeling future air and water conditions. The equity team—local community leaders who represent organizations that informally respond to flooding and air quality concerns—is developing the most accurate measure of vulnerability to identify potential impacts from multiple climate scenarios and ensure that adaptation solutions protect the region’s most vulnerable communities. Finally, the co-design team will facilitate two resident task forces that meet quarterly to discuss their values, what they see as the community’s biggest needs and problems, and what they see as potential solutions.

SETx-UIFL doesn’t rely solely on large-scale technical information to fill these knowledge gaps. When developing climate models, the team also plans to incorporate the knowledge of residents who live with the very issues being studied.

These resident task forces will inform both the climate models and the proposed infrastructure solutions. While climate models are unavoidably technical, the models coming from this project will produce future scenarios that incorporate local knowledge and will track metrics residents say are important to their community. This means that the climate models will make sense in a local context and will be producing the most accurate and useful data for local communities. For example, the research team will collaborate with residents and local organizations to imagine infrastructure that adapts to these future climate scenarios in ways that align with community’s needs and values.

This novel approach of incorporating local knowledge and engaging the community directly to find solutions sets SETx-UIFL apart from most climate modeling and adaptation efforts. Instead of envisioning climate change as something that simply happens to communities, it anchors its work in local knowledge and values. Residents are not bystanders but active participants in producing community resilience. “This is pretty different than more typical research approaches, which might collect data without first consulting the local community, assuming it will be useful and relevant to them,” said Katherine Lieberknecht, an associate professor at UT Austin’s School of Architecture and the leader of the co-design team.

Ultimately, the findings from the Beaumont-Port Arthur region can provide a model for how other under-resourced urban centers along the Gulf Coast can best adapt to climate change. The project also hopes to demonstrate a new approach to climate modeling. Where traditional projects bring in outside experts, conduct a study, and prescribe solutions to communities, the SETx-UIFL approach offers an alternative model. Its focus centers on the knowledge of those who some might consider the true experts—residents—to co-produce data that can inform climate adaptation solutions. By showcasing the power of community-engaged research for climate modeling and adaptation, the team hopes to provide a research framework that can be implemented in other coastal communities facing similar air quality and flooding issues.