In many ways, Juliet Whitsett is a perfect fit for Planet Texas 2050, an interdisciplinary University of Texas at Austin program focused on climate resilience and adaptation. The independent artist and community art educator is passionate about nature and has an instinctive appreciation for the scientific method she cleverly weaves into her creative process. She is also a UT graduate and longtime Texas resident who has worked throughout the region to build awareness about the state’s fragile ecosystem.

Yet it was southwest Wisconsin where her appreciation for the natural world was born. “I grew up close to a state park,” she said, referring to Governor Dodge State Park, 50 miles west of Madison. “We went almost every day in the summer. My mom loved to swim, and we would go and swim and then we would hike. In high school, that's where my friends and I would hang out.”

Whitsett studied art education at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and eventually made her way to Austin, where she earned a master’s in community-based art education at UT. Along the way, she continued her work as an environmental educator, including jobs at the Austin Discovery School and Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center and as a VISTA volunteer at Austin Community Gardens.

It was through her local work as an art educator and environmental activist that Whitsett met Tim Keitt, a professor of integrative biology on Planet Texas 2050’s (PT2050) leadership team. “Tim asked if I was interested in partnering with more scientists at UT to help make Texas sustainable by the year 2050,” Whitsett said. “I was like, please, that sounds amazing.”

She applied for and received one of seven 2022 – 23 artist fellowships, which are central to PT2050’s Creative Collaborations initiative.

“We were first introduced to Juliet’s work through her Biodiversity of Texas series, which incorporates visual and experiential elements to draw public attention to biodiversity loss and conservation,” said Heidi Schmalbach, PT2050’s program director. “She was already steeped in and passionate about these issues and was very comfortable engaging with scientists as part of her creative process.”

Whitsett is now collaborating with a PT2050 research team on graphic advocacy that can help Texas residents identify disease-carrying insects, which are an increasing problem due to a warmer and wetter climate. She is also working with PT2050 on imaginative new ways to engage citizen scientists of all ages, like the adaptation of her "Really Small Museum" to a mobile version focused on environmental and ecological art that can be used in community education and other activities throughout Austin.

As a fellow, Whitsett not only has more support to continue her work as an independent artist and community art educator, she can also join forces with the program’s researchers and propose collaborative projects. “Juliet is an exciting collaborator for Planet Texas because she is so skilled at bringing people together and using her multiple artistic talents to raise awareness and inspire action surrounding critical environmental issues,” Schmalbach said.

Whitsett returned the compliment. “PT2050 has really attracted scientists and researchers—and artists—who are about collaboration,” she said. “Even before my fellowship with PT2050, I was initiating partnerships with scientists, artists, community organizations and naturalists who were doing great work. PT2050 has been an incredible way for me to continue to engage with a larger community. It's been a way for me to connect and work with even more people who are making a difference.”

In Her Nature

According to the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD), there are approximately 75 endangered and 150 threatened species in Texas alone, lists that continue to grow every year. The inventory is as diverse as it is voluminous, from well-known “charismatic megafauna” (black bears (Ursas americanus) and hammerhead sharks (Sphyrna mokarran)) to obscure bivalves (Texas hornshells (Poenaias popeii)) and sandbank pocketbooks (Lampsilis satura)).

And those are just the flora and fauna in greatest peril. There are a staggering 1,300 more listed as Species of Greatest Conservation Need, “generally those that are declining or rare and in need of attention to recover or to prevent the need to list under state or federal regulation,” according to the TPWD.

“If you take a part out of the system, out of a machine, of anything, you don't actually know how that's going to affect the whole thing,” Whitsett explained. “[Maintaining] the balance and making sure that there's space for all of these species to do their part is the way that we maintain the health and wellness of an environment.”

Whitsett’s signature series, Biodiversity of Texas, is a collection of digital prints of the state’s endangered or threatened species. There are currently 52, with more on the way. “Any species you deep-dive into, you find out something so fascinating about each of them,” she said. “And then there are experts on each one of these things—I love that.”

Whitsett’s passion for—and curiosity about—the plants and animals her art illuminates is evident when she discusses them, as does her appreciation for the scientists who study them. “If I could go back in time and be a scientist, I’m pretty sure I would study freshwater mussels,” she said. “They’re so fascinating. Their lifecycle is amazing. I call them freshwater saints: they're cleaning the river."

Among these saints—often called the “livers of the rivers”—are some of the most colorfully named creatures in the state, or, indeed, anywhere. There’s the threatened Texas pigtoe (Fusconaia askewi), which is endemic to a small area on the Texas-Louisiana border and might resemble a pig’s toe from a certain angle, in a muddy river. There’s the threatened Texas pimpleback (Quadrula petrina), which, ironically, rarely suffers from acne. And then there is the fatmucket, which sounds more like a Gloucester epithet than a canonized Samaritan. “Fatmucket is a compliment!” Whitsett said, laughing.

Texas fatmucket (Lampsilis bracteata) – threatened

Going Off Colors

Whitsett’s unique style owes as much to serendipity and necessity as intention. “I started out by acrylic painting, and then the pandemic hit,” she explained. “Like many of us, we were trying to work and help our children with online school. Honestly, it was too hard to paint because there were so many stops and starts—the paints were constantly drying on the brush. So I started experimenting with digital. I loved the crisp lines and ability to play with minimalist geometry. It was a new way to work; it really suited my aesthetic.”

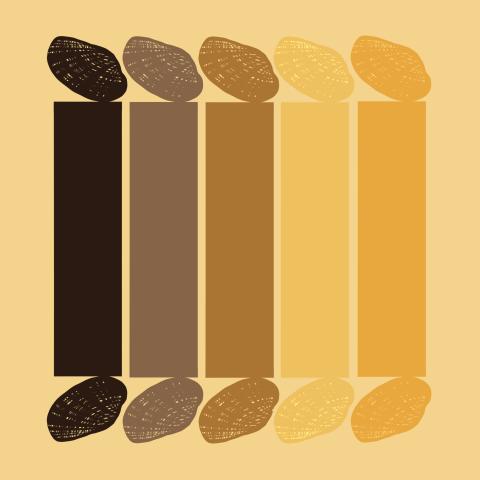

To create her Biodiversity of Texas series, Whitsett sampled colors from crowd-sourced images of the plants and animals. “A lot of these species have a lot more colors, but I look for the standout [shades],” she explained. She then draws from those hues to create a limited color palette, like this one for the endangered black lace cactus (Echinocerous reichenbachii var. albertii):

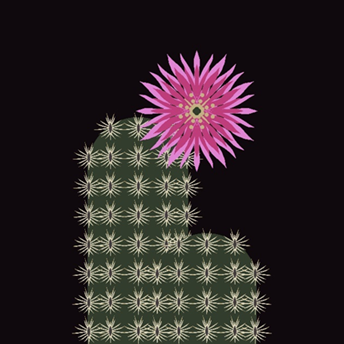

Finally, using only the limited set of colors from the palette, Whitsett creates simple yet stunning digital images.

Whitsett’s art is unique, modern, and accessible, featuring clean lines and plenty of earth tones (naturally). Her Biodiversity of Texas prints are occasionally Escher-like, often geometric and symmetrical, always recognizable. “I like to stay true to the species,” Whitsett said. “It's a way of investigating and understanding them better.”

Knowing that so many species are on the verge of extinction in Texas alone can be demoralizing. Whitsett’s goal is to bring awareness to the issue. “I think many people want to help, but don’t really know where to start,” she said. “The reality is that we all have talents we can bring to the table. I started with what I could contribute. My installations and art are an attempt to create experiences so that we can better understand issues, species, experts and solutions that we don't usually see and maybe never knew about.

“The point is, often we don't necessarily know what we need to care about unless we personally experience it somehow. For a long time, artists have been the first to call out injustices or issues. For me, the fact that more and more artists are starting to focus on these ecological issues is really saying something: artists play an important role in resilience.”

To learn more about Juliet Whitsett or purchase a piece of her art, visit her website. 5% of proceeds are enthusiastically donated to support endangered and threatened species.

To learn more about Planet Texas 2050’s artist fellowship and other ways to collaborate, contact program director Heidi Schmalbach.