Geology Professor Jay Banner, one of the authors of the federally mandated climate report released this past November, sat down with Spectrum News Austin’s Karina Kling to talk about what the climate and economic predictions mean for Texas and the southern U.S.

A lightly edited transcript follows.

Karina Kling: Jay Banner is a professor at the Jackson School of Geosciences at The University of Texas at Austin, is the director of the Environmental Science Institute, and is also a contributor to the national climate report.

First, which part of this did you co-author?

Jay Banner: This was the chapter on the Southern Great Plains, which is the region that includes Texas, Oklahoma, and Kansas. We focused on the regional impacts that we can expect.

Kling: We’ve heard some very alarming statistics — in general and for Texas in particular. The report specifically mentions Hurricane Harvey and how we could see similar or even worse storms in the future. What led to those conclusions?

Banner: Well, it’s a really basic concept. The physics of climate science predicts that as the atmosphere warms, the ocean’s surface warms as well, and that’s the fuel that drives the intensity and strength of hurricanes.

[As water heats] and evaporates from the oceans, chemical bonds break so the water can go from liquid water to water vapor, and that stores energy. When that water then re-condenses as a hurricane is spinning up, that energy is released. And that makes the hurricane even more intense.

It’s just a natural conclusion from the physics of climate science, that as the ocean’s surfaces continue to warm, hurricanes will likely become more intense.

Kling: Did we miss the warnings? Could a lot of this have been prevented, leading up to what we saw with Hurricane Harvey?

Banner: Actually, scientists hit it pretty well in terms of predicting where flooding would occur. There was a national water model that predicted where there’d be flooding based on the rainfall forecast, and the model did a good job. But to have those kinds of forecasts weeks out, months out — to know that this is going to be a more intense hurricane season — science is moving toward that [goal] but is not exactly in that area yet.

Kling: The report also talks about sea level rise along the Texas Gulf coast, [which is predicted to] be twice that of the global average. What does this mean for those coastal communities’ economies?

Banner: Sure, if you think about it, by 2100, global sea level average is predicted to rise anywhere between one and four feet. And if Texas is going to be higher than that average, then that means [we can expect to have water move] four, five, or six feet inland, and we have a lot of our industry quite close to the coastline.

Anywhere from Houston and Beaumont to Corpus Christi and Port Aransas, you’ll see giant oil tankers pulling into a port and unloading their crude, having it refined in place, and then being shipped out through pipelines, through ships to other parts of the world. It’s a hub for this kind of industry, and if sea level is rising, it’s going to encroach upon that industry. It’s also going to encroach upon our fresh water aquifers along the coastline.

Contaminate it with salt water, and those aquifers will not be viable anymore. It will change habitats along the coast. It’ll not only bring sea level higher but also will bring the storm surge from those intense storms like Hurricane Harvey even further inland.

Kling: What are we talking about health-wise? We’ve heard [to expect] about 1,300 deaths per year or possibly more because of rising temperatures.

Banner: It’s cascading set of health impacts from climate change. The most obvious one is heat stroke; heat-related illnesses can kill a lot of people.

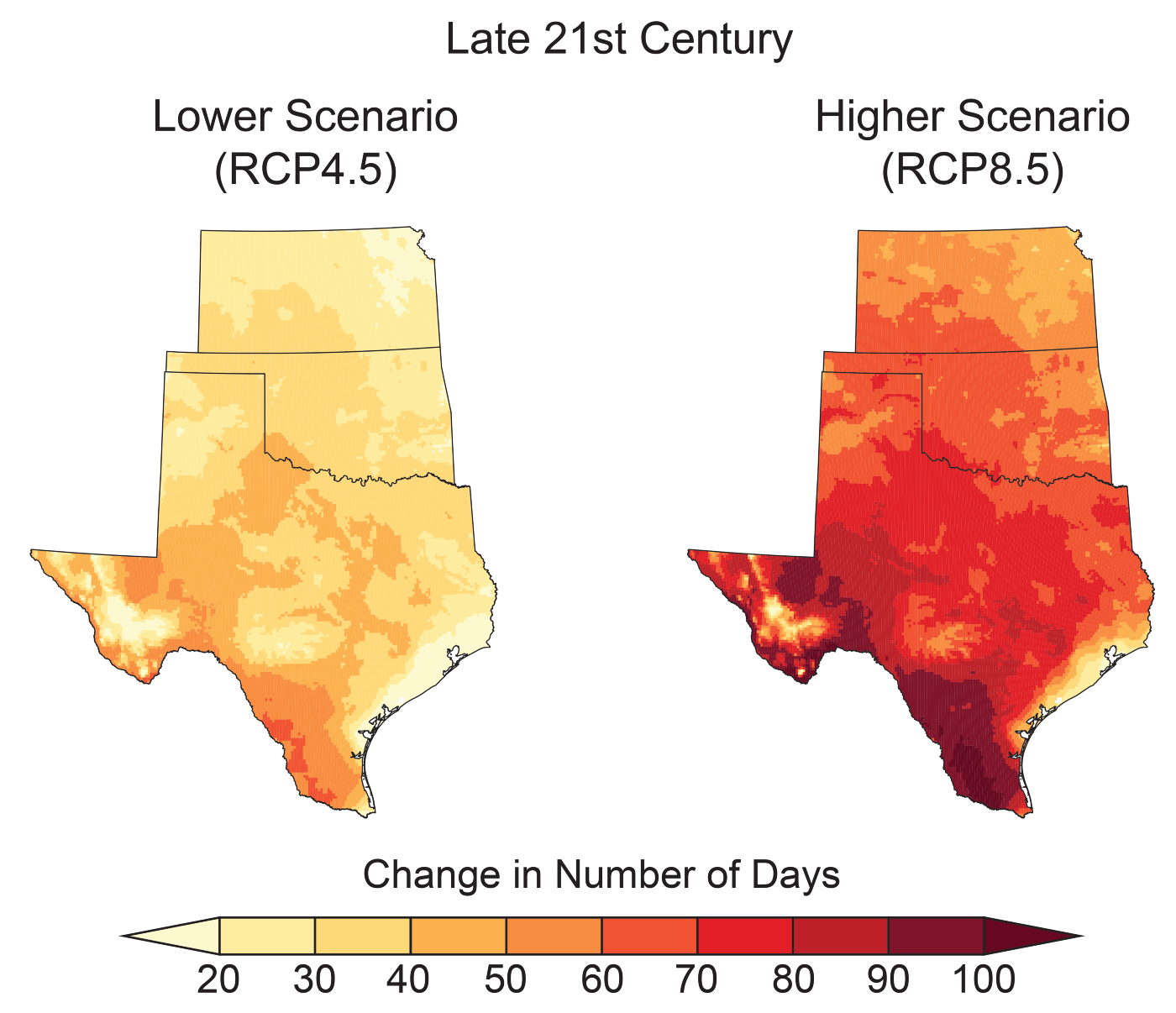

A statistic that really jumped out at me from this study is the number of 100-degree days [we can expect] in this region. This summer, it was 51 days. But the projection is that by the end of this century, if we continue on the course that we’re on, we’ll more than double that.

So think about that. Where are we going to put 110 or 120 hundred-degree days in our calendar? That’s like four months. Can you imagine continuous 100-degree days for four months? That’s from April to the end of September.

Kling: No, I don’t want to think about that.

Banner: It’s pretty remarkable. Any of these health-related impacts we see now, such as increasing heat-related illnesses, the spread of tropical diseases because the temperatures are warmer and we have disease-bearing vectors like mosquitoes expanding from tropical latitudes up into Texas — all of these things will be exacerbated. We’re starting to see the beginning of that now. The projections are that it will get worse.

Kling: So what can be done? What’s the advice?

Banner: Well, there are really two paths forward, and they’re not mutually exclusive. It’s mitigation and it’s adaptation, right? We can try to mitigate against the effects by preventing the emissions of carbon dioxide from increasing in the atmosphere by taking various steps. A lot of those will require policy change — to try and limit and put caps on how much we can emit, both as a country and as a global society.

And then there’s adaptation: given the predicted changes that are coming, how can we plan for it? How can we be ready? How can we make sure that Texas, for example, is a more resilient place than it currently is when the next drought comes along? [Consider] the drought of 2011, where we saw 10 billion dollars in loss from agriculture and livestock. Instead of seeing three- and four-year droughts, the projections are that we’ll have these mega droughts, decadal scaledroughts. [Imagine]10 or 20 years [in a row like] 2011.

Kling: The effects on farmers, the effects —

Banner: That’s right. So planting drought-tolerant crops, shifting where we plant things, being more conservation-minded with our water and how we use it and reuse it. Gray water is a great example of this. There is very little reuse of the water when we wash our hands. It just goes down the drain. Wouldn’t it be worthwhile to fill up our toilet tanks with that?

Because right now, in our toilets, we have drinking-quality water. It takes a lot of energy and water to fill our toilets with that. Wouldn’t it be logical to use the water that we’re discarding anyway, after we wash our hands, into our toilet tanks?

Kling: What’s your take on President Trump, who says he doesn’t believe the report?

Banner: When it comes to science, it’s really not a matter of belief or disbelief or what have you. It’s really what the data suggests—the best available data, assembled by — in this case—300 scientists, working across the country. Or the case of the intergovernmental panel on climate change, hundreds of scientists and engineers. There’s a really strong consensus within the scientific and engineering communities that these are the issues we’re facing.

View the complete Fourth National Climate Assessment and watch the full Spectrum News interview.

Jay Banner, Ph.D., is a professor in the Jackson School of Geosciences at The University of Texas at Austin, and he is also the director of UT’s Environmental Science Institute. His research interests center on climate and hydrologic processes and how these are preserved in the geologic record, as well as how human activity affects the sustainability of water resources.