Climate change is straining our natural and built environments as well as our social networks. Add to that a growing population — Texas’ numbers are expected to double in the next 30 years — and cities throughout our region are facing water scarcity, inadequate infrastructure, and other strains. Despite decades of research, there’s still a lot we don’t know about how natural systems (e.g., water and temperature) and human systems (e.g., health care and transportation) interact under pressure from a spiking population and weather extremes. In other words, what happens to all the cars flooded due to the record-breaking rainfall of an event like Hurricane Harvey? And how does that affect Houston’s transit system?

We’re still finding out.

We do know, however, that facts and data from research alone are insufficient when it comes to persuading people to change their behavior or persuading city, state, and federal leaders to adopt new policies. Instead, fostering a more resilient, healthy, and equitable future for all Texans requires cultural understanding and expression. We have to make space for multiple voices, perspectives, and opportunities for shared action. If we do not, we may fail to redress the historical inequities that shape existing environmental and planning policy, and we may fail to diminish the harms of climate change that fall more on some populations in our state — notably, the poor and people of color — than on others.

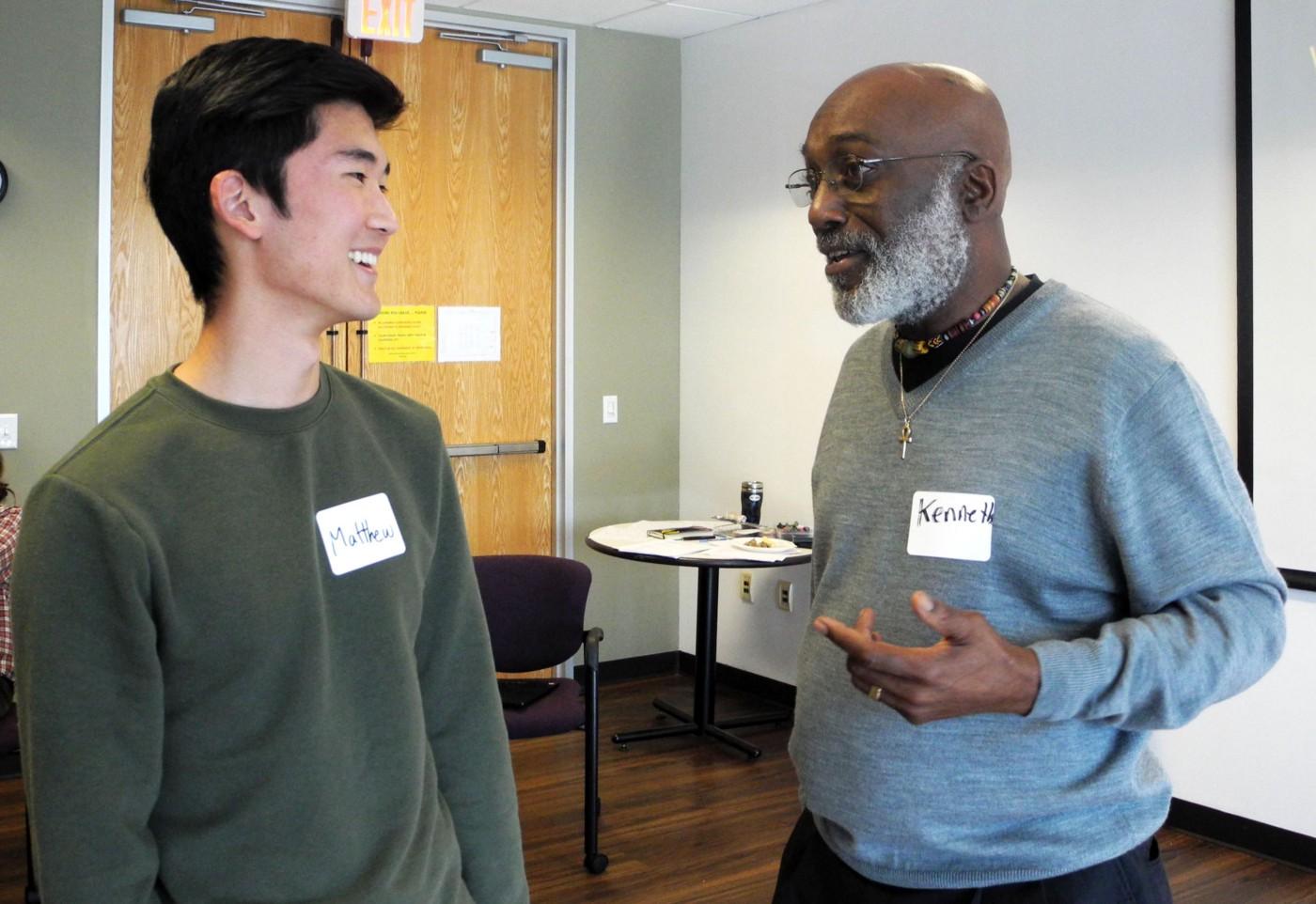

This is why community engagement, and the relationship-building at its heart, is integral for any city or institution that’s planning for climate resilience.

Typically, the first community engagement hurdle is defining community. Recall the last time you were in a conversation using the word community. Did everyone use the term in the same way? Did the boundaries of who was “in” or “out” of the community change as different people used the term? Your definition of community is important because it shapes who you include when you make decisions or seek input, as well as how and when you approach them. The same is true for climate planning.

Community engagement, and the relationship-building at its heart, is integral for any city or institution that’s planning for climate resilience.

A chorus of voices and experiences constitutes community. This chorus is sometimes harmonious and sometimes dissonant. Regardless, we must work to find common ground for realizable solutions. Finding common ground, though, doesn’t mean “converting” people to one narrative. Rather, it means listening to the languages, feelings, and personal and group histories that have brought people where they are and that guide their vision for a better future. It then means treating these languages, feelings, and histories as sources of knowledge that must be weighed on equal footing with the data and insights that researchers (or so-called experts) produce.

Community engagement also requires listening to and learning from the experiences of neighbors like the residents of Dove Springs. This neighborhood in Southeast Austin has suffered two devastating floods in the past decade: the 2013 “Halloween Flood” and another in 2015. At a Front Porch Gathering on January 21, 2020 that was co-hosted by Planet Texas 2050, UT’s Division of Diversity and Community Engagement, and Go! Austin/Vamos! Austin (GAVA), residents shared their experiences of the floods and the valiant recovery work neighborhood groups organized. The disaster exposed how Dove Springs has had less access to flood infrastructure, preparation, and response than wealthier and whiter areas of the city. This is crucial knowledge for future planning for climate-related disasters. With people and their experiences at the center of resilience planning, we can produce more equitable infrastructure, preparedness, and response strategies.

With this in mind, our Planet Texas 2050 grand challenge team is pursuing varied modes of community-engaged inquiry and strategy development. On February 29, 2020, we will co-host a Hack for Resilient Communities with UT’s Center for Transportation Research and other schools across campus. The event will bring students, researchers, and community members together to look for connections between health, transit, air pollution, and weather data in the Austin area. This hackathon isn’t just for coders and software engineers but is also open to the multiple perspectives of different disciplines and life experiences.

“Ensuring that we are increasing equity while mitigating greenhouse gases means examining the history of racial segregation and environmental justice issues in Austin.”

Participants will work in teams to pose new research questions and propose social and political actions that could improve community resilience. For example, are there hotspots of asthma in the city and are they connected to traffic and air pollution? If so, what sorts of interventions should the city undertake? Crucially, representatives from GAVA and the City of Austin’s Office of Sustainability will be present to provide context, guidance, and feedback throughout the day. By having the voices of GAVA and City of Austin in the room, everyone involved can develop their projects and ideas towards real world applicability and impact. And because the hackathon also provides the opportunity for networking and relationship-building, it increases the likelihood that those ideas and outputs will continue developing afterward.

Events such as this create closer partnerships with the City of Austin, which is also prioritizing community engagement as it revises its Community Climate Plan (CCP) this year. The Austin City Council adopted the current CCP in 2015 and committed to revising it every five years. This summer, the group revising the CCP will recommend ways to decrease carbon emissions and make Austin resilient to climate stresses as our local population surges. When the City embarked on this process, it put equity at the heart of the endeavor, declaring that “ensuring that we are increasing equity while mitigating greenhouse gases means examining the history of racial segregation and environmental justice issues in Austin.”

Your definition of community is important because it shapes who you include when you make decisions or seek input, as well as how and when you approach them. The same is true for climate planning.

To achieve this ambitious goal, the City has asked Austinites — from scientists and planners to youth climate justice activists and grassroots community organizers — to serve as advisors during the CCP revision process. At the same time, Community Climate Ambassadors are focusing on building stronger relationships with our local Black, indigenous, and LGBTQIA+ communities, our neighbors experiencing homelessness, people with disabilities, and many others. Finally, a round of community workshops began in February 2020 that expands the circle even further: they offer a chance for anyone to weigh in on issues relating to carbon emission reduction in sectors like transportation, consumption, and land use.

Most important, community engagement recognizes the rich history of grassroots environmental and social justice advocacy that has defined Austin over the decades — a history that includes successful fights to remove fuel tank farms and close the Holly Power Plant in East Austin and fights that continue to this day with contests over a proposed trash transfer station in North Austin.

As a grand challenge, Planet Texas 2050, too, has the opportunity to prioritize community-centered approaches to discovering knowledge and devising strategies for Texas’ resilience. We’re going further than interdisciplinarity in the traditional academic sense. Through community engagement, we’re treating knowledge-sharing as a two-way street — a give and take — that grounds resilience planning in the experiences of communities at the frontlines of rapid climate change and population growth.