Some activities are so common we barely take notice of them. They recede into the background of everyday life. Consider the greeting. In Texas, it’s not strange to hear a casual howdy from strangers. A nod of recognition is usually taken as a basic sign of civility. We greet one another at work and when friends and family come to visit our homes. We’re welcomed by paid “greeters” when we’re out shopping. Reporters on the daily news dutifully begin with a cheery “Good Morning!” Some spiritual traditions ask us to greet the sun or greet the day as a way of establishing rituals and habits that train us to appreciate our place in the world among others.

In addition to these verbal forms of acknowledgement, a rich tradition of greeting exists in print. Who hasn’t stood before a long aisle of colorful greeting cards, helpfully arranged into meaningful occasions, searching for the perfect (or perfectly adequate) statement to communicate one’s specific feelings?

Birthday, Anniversary, Shower, Friendship, Sympathy, Get Well, Blank.

All of these (yes, even the boldly blank variety) convey personal joy, loss, sadness, or celebration. But how do we address each other amid events on a more global scale? No arrangement of cards exists for catastrophes like floods, forced migrations, civil conflict, wildfire — the increasingly-present signs associated with global warming. Or more obviously now, no cards seem fit to greet each other during a pandemic. And yet in the midst of these admittedly ‘big’ things we go about our everyday lives. We still need to get up in the morning. We still buy eggs from the market. We still notice a pleasant breeze in the air or a cluster of birds in a field. Enduring in times of challenge often looks very much like any other day, even if how we feel inside is profoundly different. This condition requires a similarly intimate, human response, in addition to the often-impersonal policy changes that are so urgently needed. Greeting is a kind of social glue — a baseline of civility that unfolds into new possibilities for building relations and fostering compassion for others.

We desperately need to commit to such activities if we are to face massive, global challenges — whether climate change or a viral pandemic — in ways that don’t exacerbate inequality and cruelty in the world.

Recognizing a shared interest in exploring the relationship between critical thought and creative practice, Casey Boyle, an associate professor in the Department of Rhetoric and Writing, and I sought to develop a project that would allow us to collaborate across disciplines, using greeting cards as a basis for discussing climate change.

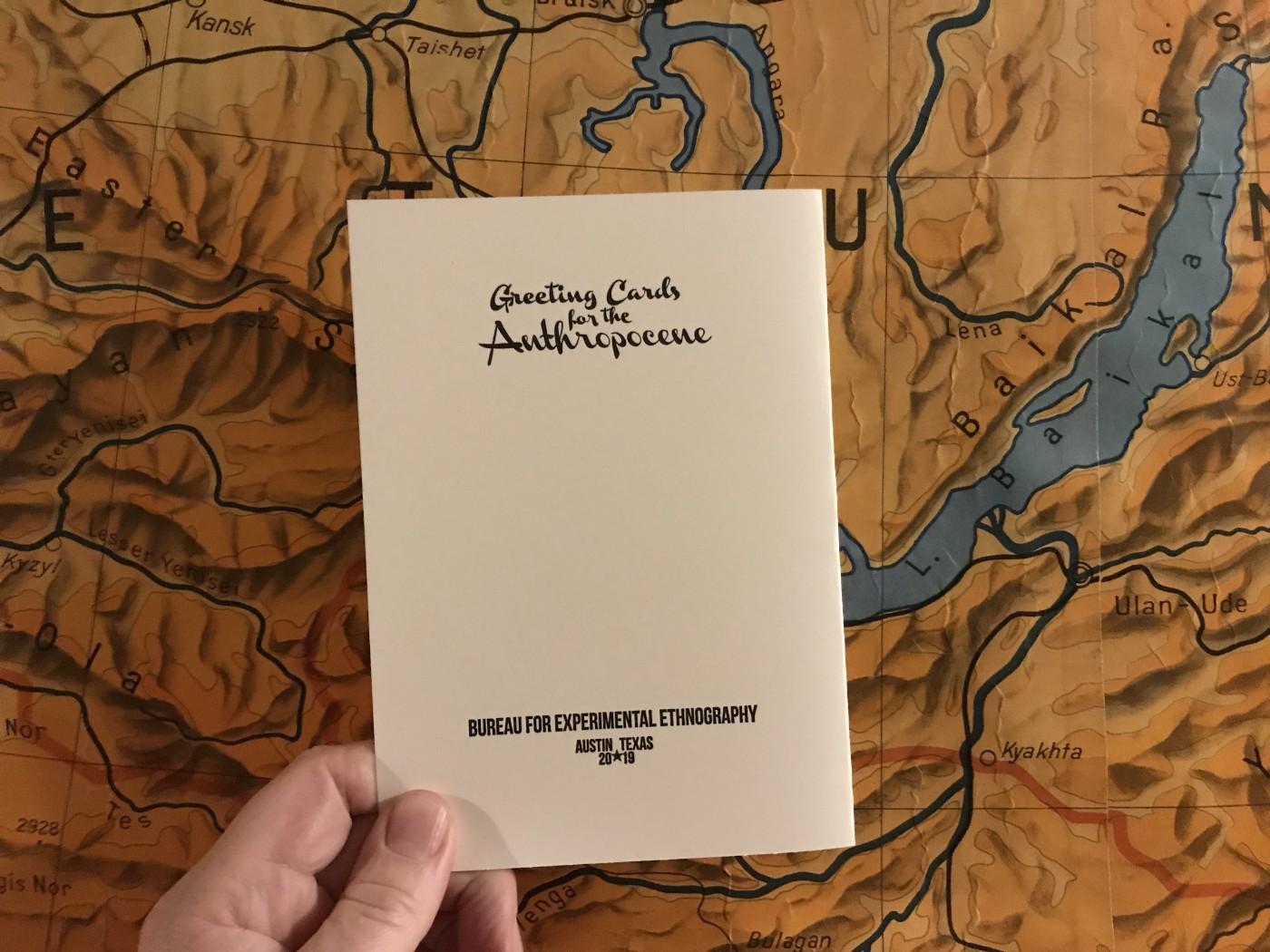

The Planet Texas 2050 initiative, a UT grand challenge that focuses on the climate crisis, offered an ideal opportunity for us to test out a truly collaborative and interdisciplinary effort. We titled the project “Greeting Cards for the Anthropocene,” for the current geological age, where human activity has been the dominant influence on climate and the environment.

Through the fall of 2019 we held numerous workshops and events to develop and print a set of greeting cards that responded to the challenges of global warming. In some ways the workshops were an end in themselves. They brought together dozens of people captivated by possibilities offered at the intersection of design, rhetoric, and anthropology. We asked difficult questions and joked about absurd greetings as we worked together and independently to design dozens of greetings. In some cases, the cards channeled a kind of collective rage. Others were more subdued and mournful. Some tried to appeal to compassion for action. As with the variety of conventional cards, we ended up with a remarkably wide array of greetings. Most have been kept as prototypes and experiments. We selected three of these prototypes and printed them by hand.

Towards the end of the semester we began the second phase of the project: sending the cards out into the world. Our goal has been to create letter writing kits and host parties where people gather to write cards in a convivial environment. The kit includes optional prompts that instruct letter writers on who to write to and that suggest what kinds of things they might want to write.

For our first experiment, in December 2019, we installed a letter-writing station at an art exhibition titled “At the Terminus” in Vancouver, British Columbia. We placed four chairs around a table stacked with cards and unaddressed, stamped envelopes, that could be sent to destinations around the world. There was one greeting card available for all. This was thematically associated with the exhibition. In future letter writing parties, letter writers will be able to choose among cards.

Over the course of three nights, more than a hundred cards were slipped into the postal stream, each one tracing its way across the world.

The activity associated with the letter-writing kit works like this: pull one addressee card and one prompt card (the first tells you to whom you should address your greeting, and the second tells you what you should write). So, for example you might pick “A Family Member Who Doesn’t Believe in Climate Change” and then a prompt card that says “Ask for forgiveness” or “Ask for solidarity” or “Describe an encounter with an animal in danger of extinction.” Some participants prefer to write letters without the use of the prompts, addressing them to whomever they please. Others shuffled through the prompts until they found one that particularly resonated with them.

Over the course of three nights, more than a hundred cards were slipped into the postal stream, each one tracing its way across the world. Some were posted to old friends, others to family or strangers. Each one traced a connection, marking a concern and lighting up a little more awareness, not necessarily about a problem in the abstract but a problem felt by someone else. This kind of interpersonal connectivity is precisely what we’re after in this project — building a sense of shared vulnerability within a frame of personal expression and interpersonal connection.

From the beginning of this project, we’ve asked the question: “What does it mean to greet one another in a time of crisis?” The greeting card invites, broadly, people to think about this question with us. It contains the weight of personal testimony and fosters a shared understanding and appreciation of what is at stake. We believe greeting cards are an expressive form that allows us to build the alliances and conscientiousness necessary to address the profound global challenge of climate change. These lessons could be expanded to consider how we lean on each other and work together in our most urgent challenge today, a pandemic.

What would your card say, and who needs to read it?