How a UT Austin research team is uncovering ancient strategies for resilience — through science, stories, and interdisciplinary collaboration

When we talk about climate resilience, we tend to focus on the future — solutions that might stave off disaster, technologies that could hold back the tide. But for a team of researchers at The University of Texas at Austin, part of the answer may lie in the deep past.

The project, called Stories of Ancient Resilience, or SOAR, is one of the core initiatives of Planet Texas 2050, a grand challenge supported by the Office of the Vice President for Research, Scholarship and Creative Endeavors. SOAR brings together archaeologists, climate scientists, biologists, geographers, humanists and artists to examine how ancient societies navigated disruption — from droughts and invasions to the slow unraveling of complex systems. By combining scientific methods with deep historical inquiry and public storytelling, the team hopes to offer new ways of thinking about resilience today.

“We’re trying to understand how complex human societies in the past have dealt with really severe disruptions to complicated systems that they established,” said Adam Rabinowitz, one of the project co-leads, a field archaeologist and an associate professor of Classics in the College of Liberal Arts. “We’re asking what they chose to preserve — and how they expressed those choices through story, practice and memory.”

Equal Ground for Humanities and STEM

SOAR was designed to ensure both STEM and the humanities had an equal seat at the table. The project is co-led by four faculty members whose expertise reflects its interdisciplinary foundation. In addition to Rabinowitz, the team includes Daniel Breecker (Earth and Planetary Sciences, Jackson School of Geosciences), Sheryl Luzzadder-Beach (Geography and the Environment, College of Liberal Arts), and Melissa Kemp (Integrative Biology, College of Natural Sciences). Together, they shaped SOAR to integrate scientific research with historical insight, cultural context and public storytelling.

“To give an accurate and complete picture of the past requires the physical work of digging up human remains and objects and layering that with scientific data about climate and environments in the past,” Rabinowitz said. “But to make sense of all this information on a human scale, we need to be able to tell stories about it, not just report the data and research.”

That perspective has guided SOAR’s research and engagement strategies. Scientific analysis — of isotopes, ancient DNA, climate proxies and ecological change — drives much of the work, but storytelling shapes how the findings are interpreted, connected across time and space, and communicated.

The goal isn’t just to analyze data. It’s to offer people new ways to imagine a livable future that is grounded in community, cultural continuity and the lessons of the past.

A Lab of the Past or Research with Reach

SOAR focuses on three major regions and time periods: the Maya period in Guatemala and Belize, the Roman Imperial period in Italy and Romania, and prehistoric and very early historic periods in Texas. In each, the team investigates how communities responded to stresses — and what strategies allowed them to adapt. In Mesoamerica and the Roman Empire, the focus is on how complex urban systems reacted to environmental and social challenges, but in Texas, the SOAR team is focused on understanding past climate and environment.

In Mesoamerica, researchers are using LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) imaging and geoarchaeology to study ancient Maya water systems and agricultural infrastructure. These networks supported large populations and persisted through periods of drought and political collapse — challenging the common narrative of a sudden civilizational “fall.”

In Romania, Rabinowitz and his collaborators are examining a Roman-period cemetery at the edge of the empire. Using isotopic analysis and ancient DNA, they’re reconstructing life in a multi-ethnic city that withstood centuries of upheaval. One striking example: Generations of individuals buried at the site show the same unusual dental wear — likely from casting fishing nets using their teeth. That continuity points to enduring practices and subsistence strategies even as the empire around them transformed.

In Texas, SOAR researchers are analyzing snail shells and small animal remains to reconstruct past precipitation and temperature patterns. This work builds on earlier Planet Texas 2050 collaborations and contributes to long-term efforts to understand how ancient climate shifts shaped life in the region. It also highlights how hyper-local climate data — like the oxygen signatures in snail shells — can fill in gaps left by large-scale models.

SOAR has already produced published peer-reviewed research on Maya water infrastructure and oral microbiomes from ancient human remains at Histria. Additional studies — on Roman diets, mobility, paleoclimate modeling in Texas, and AI-based identification of burial mounds — are underway.

The Oldest Site in the Americas — In 3D

One of SOAR’s most innovative projects in Texas is grounded in evidence of some of the oldest human history on the continent. Near Florence, Texas, the Gault Archaeological Site preserves evidence of human occupation dating back at least 20,000 years — possibly the oldest known site in North America. Using archaeological findings from archaeologist Michael Collins and the Gault School of Archaeological Research, along with SOAR’s own paleoclimate data for Texas, the SOAR team is working with Tom Chandler, a digital archaeologist and faculty member at Monash University in Australia, to create an immersive virtual reality, or VR model of the Gault landscape.

Chandler specializes in 3D modeling, virtual animation and evidence-based historical reconstruction. In partnership with SOAR, he’s using VR to model the flora and fauna of Central Texas a millennia ago, creating a dynamic landscape that visitors could one day explore in a headset — complete with sounds effects.

“It’s a reconstruction of a moment in time,” Chandler said. “It’s the closest thing we have to time travel. It’s just an illusion, of course, but it is evidence based.”

More importantly, it offers a visceral experience that can spark new debates and new questions about the past, and while it isn’t predictive, it can help inform decision-making about the future.

The SOAR team is in conversation with the Gault School’s board to seek their advice on landforms and ensure the resulting models are both accurate and potentially useful for the Gault School’s own work.

The Gault VR is part of a larger, public-facing storytelling push. The team has already designed an immersive installation called the “climate closet,” a sensory experience that contrasts familiar and unfamiliar environments through sound and visual imagery.

The team has discussed the possibility of a screenwriting competition, which could invite writers to craft interwoven narratives set in both the ancient world and a future Texas transformed by climate change.

Partnering with Indigenous Communities

SOAR also is bringing its immersive storytelling to Spring Lake in San Marcos. At Spring Lake in San Marcos — also known as Sacred Springs — the team is working with the Indigenous Cultures Institute (ICI) to weave cultural knowledge into a VR reconstruction of how the lake’s plants, animals and landscapes looked roughly 10,000 years ago. This work is one facet of a broader, ongoing collaboration with ICI that supports community-based education and cultural preservation.

That collaboration includes ICI’s teacher training program, which introduces educators to indigenous pedagogies grounded in story, land and water. Led by Marial Quezada, the program has developed new assessment tools, gathered participant feedback and documented its early impact — with SOAR’s support helping to make that possible.

“Storytelling is central to the institute,” said Quezada, also a Ph.D. student in Cultural Studies in Education at UT. “The team developed tools to assess how the participants in the program are receiving training in Indigenous approaches to teaching and learning that’s based in Coahuiltecan people’s stories, and their relationships with local lands and waters.”

More importantly, the collaboration was community-driven. “It wasn’t SOAR coming in with a pre-set research agenda,” she said. “It was: What can we support? What does ICI need, and how can we contribute in a way that’s respectful and useful?”

The partnership has also encouraged ICI to share its work in new settings. Participation in Planet Texas 2050’s annual symposium sparked broader conversations about how the institute’s community-based approach to education could resonate with other academic audiences.

It was an impetus for ICI to start presenting at conferences and engaging with scholars who are doing related work, which has also helped them connect with other indigenous-led programs across the country.

Mapping What Matters

SOAR’s Texas-based efforts include the development of a Heritage Risk Map for Travis County — an ongoing collaboration with local partners to identify cultural, historical and community landmarks vulnerable to climate disaster. The goal: ensure that places of cultural memory — such as archaeological sites, historic buildings, public artworks and institutions that preserve cultural memories like libraries, museums and archives — are factored into resilience planning.

The first phase of the map, which should be completed this fall, combines historical records with geospatial data and community input — bridging the technical and emotional dimensions of community spaces and disaster planning.

“If you acknowledge that human history tends to show that you can't hold on to everything and that things are going to change, you need to be clear about what you want to save,” Rabinowitz said. “But how does a community figure out what is important enough to save? The map is a starting point for thinking about this process.”

Cross-Training and Cultural Literacy

SOAR’s structure gives graduate students the chance to work across disciplines in a way few other projects allow. Anthropologists learn isotope analysis. Biologists dig into historical archives. Humanists learn to interpret geospatial data.

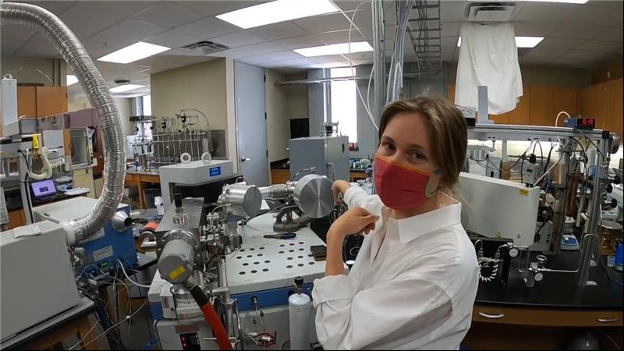

For Amber Kearns, a Ph.D. student in the Department of Classics, the opportunity to work in both the ancient DNA and isotope labs was what drew her to UT Austin from Tennessee. As an undergraduate, she double majored in biochemistry and classics and learned that she liked being immersed in both disciplines.

When Kearns joined SOAR, she quickly began building new skills by training in the archaeogenetics lab and learning digital coding pipelines for genetic analysis. She now works on isotope sampling for archaeological remains from Romania.

The experience has been eye-opening. “Even if someone doesn’t end up doing lab work in their own research, having some training is incredibly valuable,” she said. “For example, if you’re a classical archaeologist working at a dig site and you’ve had lab experience, you’ll know what to look for in samples and how to handle them properly to avoid contamination.”

Redundancy as Resilience

One of SOAR’s most striking insights is that redundancy — not efficiency — was often the key to resilience. Ancient societies that survived disruption didn’t rely on a single system or solution. For example, having a back-up source of water, or more than one means of income, such as fishing and trading.

“If your system has only one pathway, and that pathway fails, everything breaks,” Rabinowitz said. “But if you have backup systems — if you have Plan B and Plan C — you can keep going. It’s the strategy that evolution has been using since the beginning of life.”

Such backup plans mean that communities can preserve core parts of their culture and society, even when faced with major disruption. The Maya political system as it was in 1200 is gone, but Maya language, culture and stories remain vibrant today. Likewise, though the Roman Empire fell centuries ago, its laws, linguistic legacy and architecture continue to shape European societies.

These examples illustrate the kind of resilience SOAR studies — the preservation of identity and values despite profound change. Ultimately, SOAR offers more than insights into the past. It offers a new way of doing research — one rooted in complexity, community and continuity.

“Resilience isn’t just about making it through hard times,” Rabinowitz said. “It’s about protecting the core values, knowledge and identity that define a community, even when you have to let other things go. That’s what allows a culture to endure.”