I'm spending the night in the small town of Muleshoe, Texas, in the Llano Estacado, a region west of Lubbock and Amarillo. I’m interviewing farmers to hear how they talk about the environment where they live and work, the terms and phrases they use, the stories they tell.

The Llano Estacado is an extraordinarily flat place and is so dry that most of the farms depend on irrigation to supplement the sporadic and unpredictable rain and snowfall. I’m interested in how people in this part of the state think and talk about water, in particular, because our stored water will run out within a few decades at the current rate of consumption. Just when this will happen in any particular place depends on ups and downs of a layer of sand and gravel buried far below the flat surface of West Texas and the Panhandle.

The water will run out late in the century where groundwater is abundant, but it will run out sooner than 2050 in places with a thinner saturated thickness (the depth of the porous layer that holds water), and that day has already come for hundreds of farmers.

When the wells dry up, it greatly compounds the challenges of dealing with climate change, not only for farmers but also for the communities they live in — communities that depend on the farmers’ purchasing power, their produce, their community participation, and their sense of local history.

When the aquifer is depleted, that will also spell the end of locally-produced drinking water for small towns like Muleshoe and Perryton and will create a complicated sourcing puzzle for cities like Lubbock and Amarillo. This is a disaster waiting to happen.

I want to know, are Texas farmers worried about what the future holds for the local economy and community? How do they view policies designed to promote water and soil conservation? How do they see the risks they face year in and year out? And what’s up with the weather?

“Blessed to be stewards of the plentiful water”

In places like Muleshoe, it’s not a mystery why everything depends on the aquifer. Even the informational brochure on the hotel room dresser refers to underground water. It starts: “We are proud of our West Texas heritage and traditions. Our history is rooted in agricultural activities. Our land is rich and fertile. We have been blessed to be stewards of the plentiful water supplied by the Ogallala Aquifer.”

The last sentence refers to a vast aquifer that underlies 174,000 sq mi (450,000 km2) of the United States, including most of Nebraska and parts of South Dakota, Wyoming, Kansas, Colorado, Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Texas. More than a quarter of the irrigated farmland in the U.S. lies over this aquifer, but it is being drained by human uses and is most severely depleted in Texas.

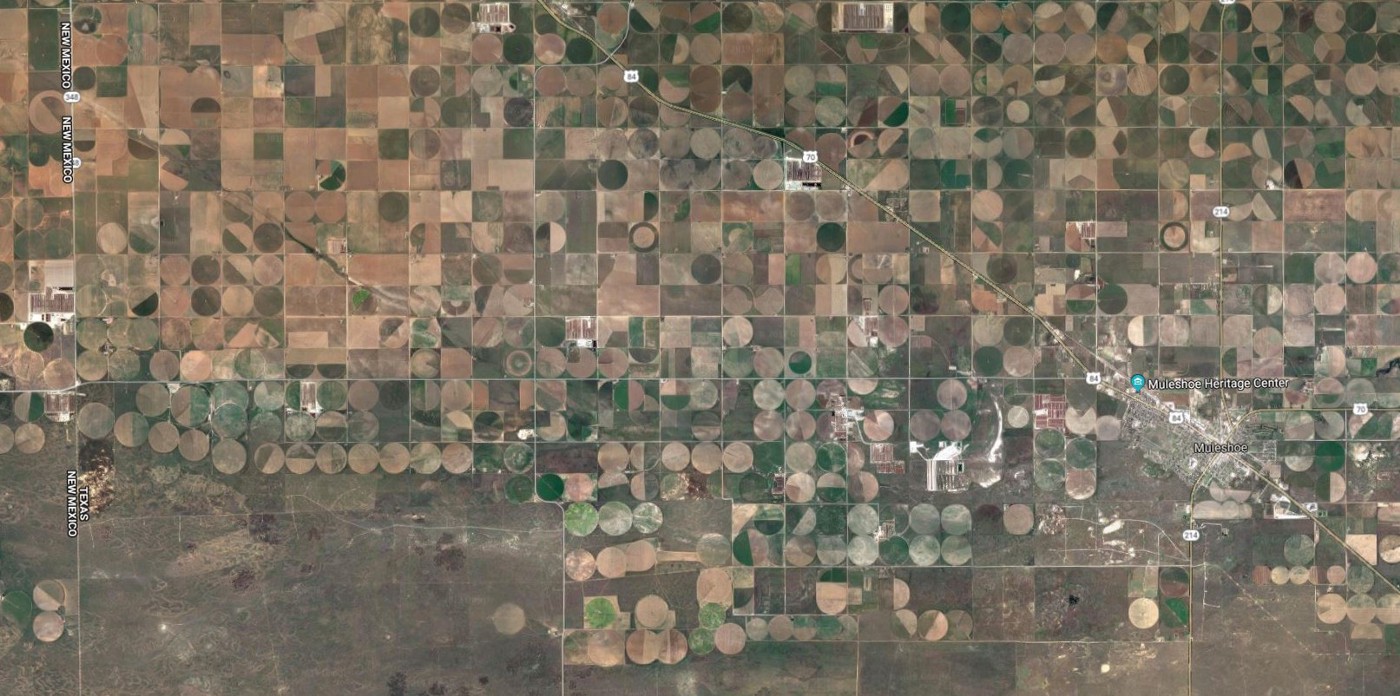

If you were to fly over this region in an airplane, you would be treated to an abstract painting — a striking pattern of circles within squares. The circles are made by long sprinkler systems, a quarter or half-mile in radius. These are “center-pivot” systems that distribute water from a layer of sand and gravel 400, 500, or even 600 feet down.

Depending on the time of year, you may see green circles on tan squares, tan circles on brown squares, or brown circles on green squares depending on what is being irrigated. Crops develop, ripen, and are harvested at different times of the year, painting the landscape with the changing hues of new growth, mature plants, seed heads (or cotton bolls), and stubble. Even a harvested field can take on different colors depending on whether the owner tills the land or leaves the stubble in place to preserve the soil.

The water that paints this abstract art is sometimes called “fossil water” because it has been percolating through that buried layer of sand and gravel for thousands of years, trickling slowly from west to east. In fact, the Ogallala Aquifer has such a slow recharge rate (the rate it refills itself) that once it’s depleted, it will take thousands more years to replenish. The day of reckoning is not far off.

The water table has already dropped by more than 150 feet in major parts of Dallam, Sherman, Ochiltree, Parmer, Castro, Swisher, Lamb, Hale, Floyd, Crosby, and Lubbock counties, and by over 50 feet in many of the adjoining counties. Someone flying over this region in 20 to 30 years will see a different view than the one above. Many of the circles will be gone, and the majority of the farms, which are now moderately profitable, will be in a financially precarious situation. They will have to depend on rain and snow in a climate zone where rain storms often come too soon or too late, bringing too little or too much moisture, and the winter wheat may or may not get enough snow to protect and water it.

My interviews with farmers in Bovina and Muleshoe give me the impression that groundwater is on everyone’s mind. Even crops like cotton that are not particularly thirsty need watering at key times of the year, and the wells are running dry.

“Gonna dryland this mess”

The next day, I’m sitting in the Stripes convenience store in Muleshoe, talking to a farmer (let’s call him Dirk) whose wells have done just that.

Dirk says that back in the 1950s when his dad moved to Parmer County, “you could run an irrigation well that’d pump a thousand gallons for 200 dollars. Well now it’s — I haven’t watered anything. I’ve been dryland now for about 10 years… I quit when the water got down to about 350 gallons, and I was losin’ my butt! And my dad didn’t want to pay any of the help, what with the expenses. So I say ‘fine, I’m gonna dryland this mess.’ So that’s what I’ve been doin’.” What he means by “dryland this mess” is to depend entirely on natural precipitation to run the family farm.

When I arranged the interview over the phone, he asked ironically if I had a “cryin’ towel.”

A typical Texas farmer risks hundreds of thousands of dollars each year paying for seed, fertilizer, equipment upkeep and other overhead costs just to hold onto a middle class (or more modest) income.

When it works, it works. When it doesn’t, the farmer can recoup some losses from crop insurance (assuming it was purchased at the beginning of the season), then the next year’s outlays have to be covered by cutting into savings or borrowing. Two or three crop failures in a row means bankruptcy and the loss of a farm that has been in the family for generations. Dirk is only half joking about the “cryin’ towel.” The shift to dryland farming will mean smaller crop payments in a county where the median household income is less than $50,000.

“Not a big believer in climate change”

Farmers in this part of the state say they don’t believe in climate change, but most of them have stories about how the weather is changing over time — summers are hotter, spring comes earlier, storms are more severe.

“The thing I’ve noticed and I can almost document, um, is the seasons are evolving. Fall comes later and so does spring. Uh, I played in the high school marching band, and we froze our rear ends off at football games, and football season is over before it’s even cold weather nowadays. Uh, we used to plant milo, grain sorghum, the first of May. That was just the day, you know, and corn the first of April. Well now May one is optimum time for corn, and uh, spring comes later but so does winter. I have no doubt that that’s happening.”

This comes from a farmer whose property borders on the Oklahoma panhandle. A few minutes before saying this, he let me know, “I’m not a big believer in climate change. I mean, I can’t tell the difference between 99 and 100 degrees, if I didn’t look at the thermometer in my pickup. I mean, I’m sorry, but I’m just not a proponent of that.”

Another farmer who doesn’t believe in climate change tells me: “Our weather seems to be more violent. It’s drier, it’s hotter, it’s windier. I mean everything is more extreme.”

They laugh at the idea of global warming, and they’re sure that whatever is happening, it’s not our fault. If there’s a change, it’s a change in the weather, not the climate, and the scientific facts they rely on are the ones that indicate the earth has always changed.

When scientists talk about “climate change,” they are not just talking about warming but also about shifts in seasons, precipitation totals, and storm events. They aren’t denying that the earth has changed for reasons that had nothing to do with people, but now it does.

In West Texas and the Panhandle, such nuances are unknown. The term “climate change” is understood to mean “global warming,” and that phrase is viewed as being out of touch with local needs and experiences. Whether this misunderstanding is caused by the failures of journalists or the rhetoric of politicians or a weakness in the school curriculum doesn’t really matter.

What matters is that people here are worried about the exact sorts of changes that climate scientists are worried about. There is a communication impasse, and solutions are out of reach until we find better ways of talking about the weather.

A common language for dealing with this “weather” change will help increase resilience here, in an area that is already economically precarious, and throughout the state. Whatever our politics, economic risk caused by resource depletion and unexpected weather extremes is something we’ll have to deal with.

“There’s no conservative attitude”

Now I’m getting an earful from a farmer at a winery north of Lubbock.

“Our attitudes about water use are literally insane. They’re, they’re crazy! Just like it’s finders-keepers, losers-weepers. There’s no… There’s no conservative attitude.”

The last words are spoken slowly and deliberately, as if he wants the listener to think about them for a minute. He knows that using “conservative” to mean “pro-conservation” is a provocative way of talking. The people I meet are suspicious of environmental conservation because they are staunch conservatives.

For them, conservation means someone telling a landowner what he (most farmers in this area are men) can do with his land. This farmer outside Lubbock has identified a paradox in this attitude, and he wants to get people talking about it.

He is suspicious of government policies designed to conserve “the environment” but is also aware that policies designed to ignore environmental constraints actually hasten the destruction of the traditional lifestyles cherished by conservatives.

As an example, groundwater conservation districts are part of the puzzle he’s calling insane. In 1949, the Texas legislature approved the creation of groundwater conservation districts to “provide for the conservation, preservation, protection, recharging, and prevention of waste of groundwater, and of groundwater reservoirs or their subdivisions.” There are currently 98 of these districts, and they cover most of the state. Their existence would seem to ensure the conservation of Texas groundwater, but their powers are too narrowly limited to do this.

They “may not adopt any rules limiting the production of wells, except rules requiring that groundwater produced from a well be put to a non-wasteful, beneficial use.” Beneficial use can be anything that makes money, including pumping out the groundwater, bottling it, and selling it to people in places where water is abundant. In other words, under Texas law the legal meaning of “conservation” is tangled up with “consumption.”

The chapter of the Water Code that authorizes groundwater conservation districts only uses the word “consumption” one time in connection with groundwater use. Instead, the word “production” appears 66 times. The word “extraction” is missing entirely. The implication here is that Ogallala water is being extracted and consumed, but Texas law not only permits this, it ensures that legal arguments must call this “production,” which implies an unlimited process. Whether this is “literally insane” or merely misguided, we need to fix the vocabulary we use before we can solve the problem.

By the end of my Texas Water Stories project, I hope to provide scientists and policy makers with a better understanding of the complicated meanings of words like “groundwater,” “irrigation,” “weather,” “climate,” “conservatism,” “conservation,” “production” and “consumption.” The point is not to say what these words should mean, but to explore what they do mean, in real places across the state, and how those meanings are evolving in response to changes in the weather and the economy — to open up the debate by shining some light on weird verbal manipulation. By paying attention to environmental communication, I hope to help bridge the gap between environmental science and common sense.