When UT operations research and industrial engineering graduate student Kyoung Kim approached his professors in 2017 with an idea to use logistics to help with disaster planning, he had no idea the biggest disaster in a century would, in a few months, ravage the Texas coast.

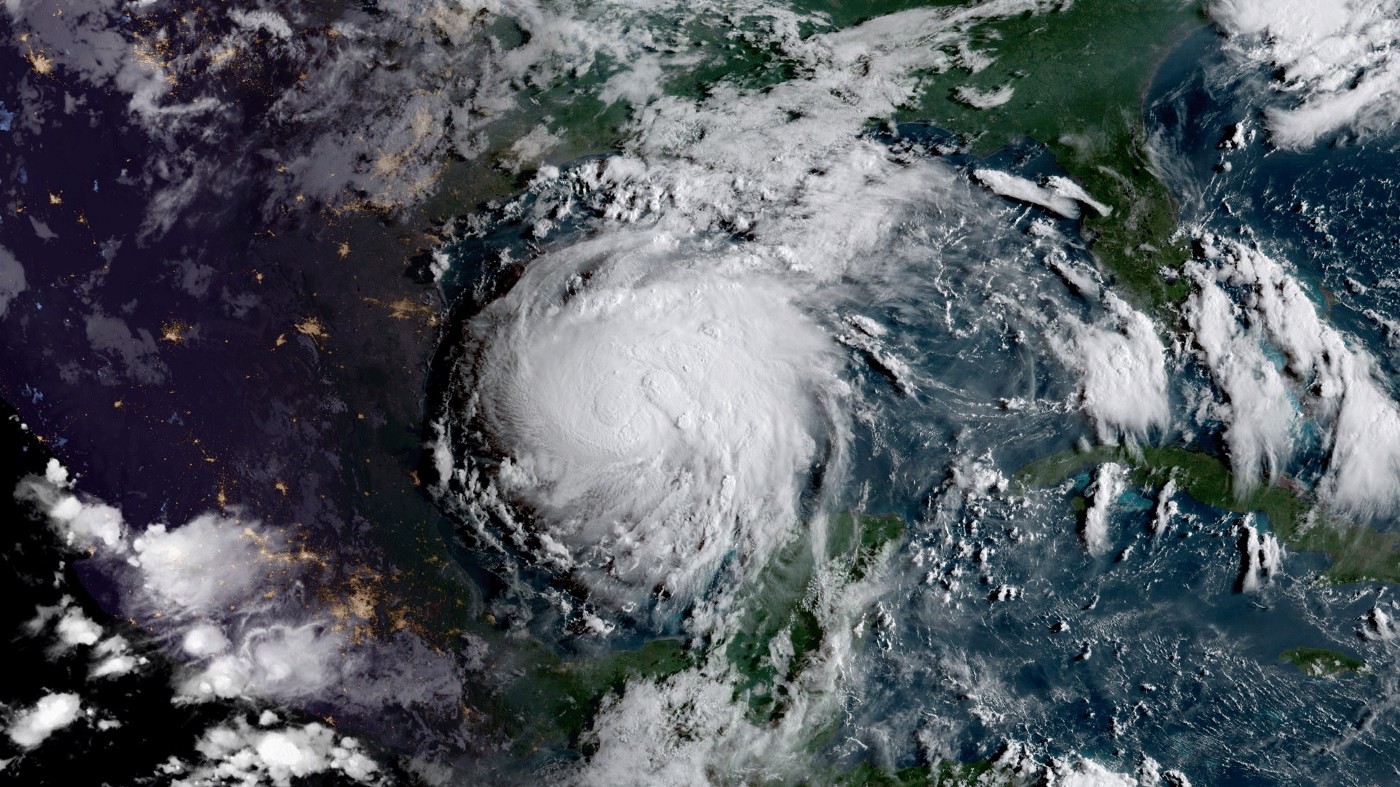

That August, Hurricane Harvey dumped as much as 50 inches of rain on the eastern half of the state. Whole cities were under water, and many were without power and running water for days — escalating the need for the type of help that Kim had imagined.

His advisor, Associate Professor Erhan Kutanoglu, had for most of his career used logistics to look at how to optimize supply chains so that businesses could make more money.

But here was a humanitarian crisis in front of him where he could lend his expertise.

“I said, ‘I’ll drop everything,’” Kutanoglu remembers. “I told Kim, ‘Don’t worry about solving a potentially made-up disaster logistics problem that has been solved many times. Let’s look at something new, something relevant to current events. Let’s focus on Texas and the tangible problems we can solve.”

Kutanoglu was flipping through news articles after the hurricane to see what kinds of logistics problems the crisis had created when he came upon a story in the Washington Post about issues evacuating hospital patients during the storm.

They made a decision.

They would create the most efficient, comprehensive model possible to move vulnerable people to safety during life-or-death crises.

Evacuating the storm

Hurricane Harvey made landfall on the Texas coast near Rockport. While the damaging winds ravaged the coastal town, it was the rain bands farther north that dropped inches upon inches of water on cities like Port Arthur, Houston, and Beaumont.

Lori Upton, who manages emergency response for the nonprofit Southeast Texas Regional Advisory Council (SETRAC), said they were surprised and devastated by the amount of flooding. The organization helped evacuate hospital patients from a 25-county region during the storm, but because roads were inundated with water, they had to rely on helicopters to get people out of the area instead of ambulances.

“It’s difficult to try to move that many people when you have limited number of helicopters, and you are waiting for someone to come in and assist you,” Upton says. “In a situation like that, when you’re looking at 72 to 96 hours-notice to move millions of people out of harm’s way, your time is very critical. Anything that would make that faster and more precise would be beneficial.”

Kutanoglu and his team have been working with SETRAC over the past three years to build a more efficient model that would show, very clearly, where flooding is expected during major storms. SETRAC could then use that model to decide where to stage assets like ambulances and how to evacuate patients.

The project, which is supported by the National Science Foundation’s Coastlines and People program, is part of Planet Texas 2050, a UT grand challenge that seeks to make the state more resilient in the face of unprecedented growth and climate change that will make unpredictable and devastating storms like Harvey more common.

Today, when a hurricane forms in the Atlantic Ocean, the National Hurricane Center puts out a forecast showing its probable size, strength, and path — the familiar cone of uncertainty most of us have seen on TV. Hospitals and health care facilities in the path of the storm usually make their own decisions about what to do with their patients if they anticipate flooding in their area. When they need extra help and resources, they call on organizations like SETRAC.

These decisions often happen in a silo, facility-by-facility, and they don’t take into account the overall picture of flooding across the state. This creates inefficiencies that could be costly, Kutanoglu surmises, and they also don’t factor in the hallmark characteristic of a hurricane — uncertainty.

Already, three named storms have spun up in the Atlantic Ocean, including Tropical Storm Cristobal, which struck Louisiana this week and became the earliest ever third named storm to form in any Atlantic hurricane season.

Winds shift, and with them, the path of the hurricane. Sometimes the storm moves slower than anticipated, as it did with Harvey, which means it sits parked over an area for longer, dropping more rainfall than originally predicted.

Building a better model

Predictive models that hospitals and other agencies rely on today don’t take into account all potential storm scenarios, and they don’t include a final output that recommends logistics decisions about evacuating their patients.

Kutanoglu’s team is tackling these problems by bringing in expertise from across UT’s 40 acres.

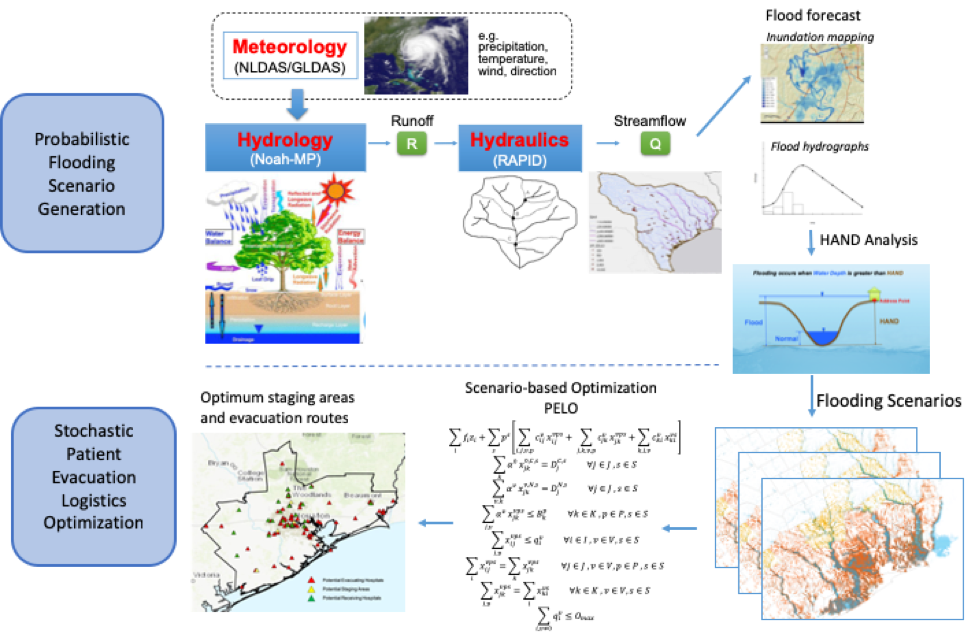

Hydrologists, using state-of-the-art flood modeling, will first determine where and how much rain will fall so they can create a map of hotspots showing areas most in danger.

Next, engineers will use something called stochastic modeling, which incorporates randomness to factor in the storm’s uncertainty — in other words, to predict how those danger zones could vary based on changes in the hurricane as it moves closer to land.

Finally, logistics experts will figure out how to deploy ambulances and medical personnel and evacuate patients in the most effective way taking into account all variables.

These things are expected to occur seamlessly, as part of one integrated model. The final output will include the best evacuation routes to avoid flooding.

When the model is finished, the hope is that it will also allow state agencies, hospitals, and healthcare facilities to make informed decisions about where to stage assets like ambulances and large ambuses — or ambulances that can fit around 20 patients — before hurricanes, as well as what hospitals should evacuate patients, how many, and where they should be taken based on facility capacity and capabilities.

Accomplishing all this will require the computing power of the machines at the Texas Advanced Computing Center — which, through a system called MINT-T created as part of Planet Texas 2050, will be able to perform the integrated modeling required.

“We are really trying to get the whole decision-making process down to 10 or 15 minutes,” says UT mechanical engineering professor John Hasenbein, the team’s expert in stochastic modeling.

To test the model, the research team started by using the computers to recreate Hurricane Harvey to see how they would have made evacuation decisions if the system had been up and running in 2017. Next, they tested it on computer-created hurricanes to see how it would function. The final stage will be using it to make real-world decisions in real-time during an actual hurricane season, which Hasenbein says could be as soon as this year.

Kutanoglu says the hope, eventually, is to create a software package that interfaces with maps and Excel files that agencies like SETRAC could use to help with evacuation, but they haven’t figured out yet what that will look like. For now, the computers at TACC will perform the calculations and provide the raw data to SETRAC to use, informed by their own expertise.

SETRAC has been an asset in helping to fine-tune the team’s model, Kutanoglu says. Researchers had to make sure they were asking the right questions and that the finished product would accomplish something beneficial in an actual storm.

“Sometimes models aren’t realistic, and they aren’t taking into account what real life is like,” Upton notes. “But these guys have listened and they have taken information that we have given them from previous experiences and they adapted their model. I think they are doing a fantastic job.”

SETRAC says they are looking forward to the finished product and how it will be able to help them in future hurricanes.

“Hopefully, they will be able to make better, faster, less costly decisions and evacuate people to safety more quickly,” Kutanoglu says.

An unusually active season

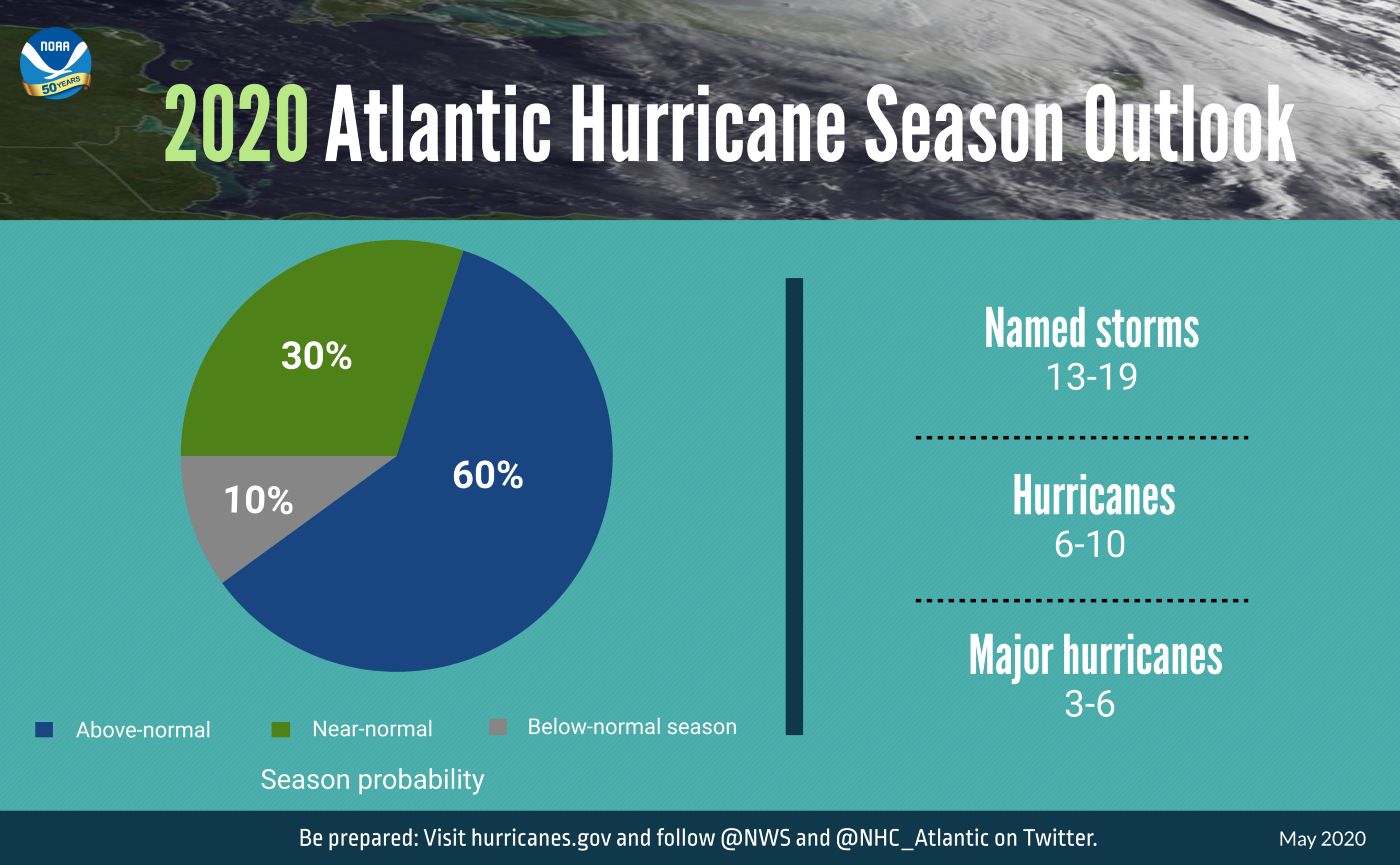

On May 21, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration put out its prediction for this year’s hurricane season, which started June 1. They are predicting anywhere from 13 to 19 named storms, which would make it an “unusually active” hurricane season. The average number of seasonal hurricanes is 12.

Texas, which typically sees an average of two named storms from June through Nov. 30, could see as many as four this time around. Already, three named storms have spun up in the Atlantic Ocean, including Tropical Storm Cristobal, which struck Louisiana this week and became the earliest ever third named storm to form in any Atlantic hurricane season.

Because of climate change, the storms that do actually make landfall could be more unpredictable and carry with them more devastating rainfall, a trend we’ve started to see in recent years.

“Studies predict that these types of events, not just hurricanes but other events like heavy rainfalls and thunderstorms, will get more variable,” Kutanoglu says. “Storms will be more intense. Wet will be wetter, and dry will be drier. That is basically what variable means — extreme temperature, extreme weather, extreme rain.”

This year, the pandemic is expected to further complicate disaster response.

Kutanoglu says emergency officials can no longer pack a bunch of evacuees in a crowded stadium because of social distancing requirements. EMS may not be able to use the large ambulances that fit 20 people to move people from hospital to hospital. Some hospitals may not have the needed beds or resources to take on additional patients.

He and his team are working on how they can fit these new pandemic scenarios into the current model.

Suzanne Pierce, a UT research scientist who works on integrated modeling, says the computers at TACC are particularly primed to handle these kinds of multi-hazard scenarios, which will become more common in the future as Texas’ population grows and the climate changes.

“In this multi-hazard world that we are entering, we know that our response systems are being challenged to respond at scales that we have not seen before,” she says. “They are likely to be challenged to respond simultaneously to more than one type of hazard — fires and floods or fires and COVID or an epidemiological event. Each of these hazards has its own character. It has its own subject matter expertise that comes to bear. Our aim is to streamline it so we can determine the best way to save lives and keep people safe.”

Kutanoglu agrees. “Seeing its potential use in real life is really quite motivating.”